This article was written by Indian journalist Pawan Dhall for the Sogicampaigns site.

The views expressed therein are those of the author

On September 6, 2018, the Supreme Court of India irreversibly read down Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, a British era relic that carried 71 years into independent India. This was a much anticipated victory for the queer movements in a socio-legal battle a quarter of a century old. Primarily, the verdict decriminalized non peno-vaginal sexual acts among consenting adults in private. But it was crucial also for destigmatizing non-normative sexual orientations and gender identities at a larger social level.

This was the second time that Section 377 was read down. In 2009, the Delhi High Court, in response to a writ petition filed by Naz Foundation (India) Trust in 2001 and later joined in by co-petitioners Voices Against 377, declared that Section 377 was unconstitutional. But after several religious entities appealed against this verdict, in a much criticized move the Supreme Court reinstated the law in December 2013. The apex court’s recent change of heart was an outcome of a long-drawn process that involved review and curative petitions, and a host of fresh writ petitions by a number of queer individuals and allies. Key verdicts around transgender citizenship rights (in 2014) and the right to privacy (in 2017) by the same court, and earlier central government legislations on sexual assault issues also played a significant role in weakening the argument in retaining Section 377.

But however important these legal stepping stones, the queer movements’ endeavours outside the courts of law were equally important in Section 377 finally being read out of queer lives in India. Campaigns and discourses around gender and sexuality influenced public opinion in significant ways that in turn had a bearing on the legal articulations inside the court. Beginning with the publication of India’s first ‘pink resource book’ Less Than Gay in 1991 and a protest demonstration against police harassment of queer people in Delhi in 1992 – both led by AIDS Bhedbhav Virodhi Andolan – queer rights initiatives went on to encompass landmark conferences; crucial documentation and narration of queerness in Indian cultures through films, books and plays; rainbow pride marches; sensitization of healthcare and legal aid service providers; and open letter campaigns.

Building solidarity with women’s, child rights and other movements strengthened the queer movements. Be it the nuance in demanding reading down of Section 377 rather than an outright repeal, protesting the ban on the film Fire in 1998-99, dealing with the Lucknow arrests of sexual health and queer activists in 2001, or broad-basing the legal battle through the formation of Voices Against 377 collective in 2006 and engagement of allies like parents of queer people and mental health professionals in 2010-11– these were all enabled through persistent bridge building. The ‘Global Day of Rage’ campaign after the shocking reinstatement of Section 377 in 2013 was also facilitated by such intersectional collaborations.

The latest Supreme Court verdict has drawn favourable responses from the judiciary (example, in the matter of a lesbian couple in Kerala winning the right to live together) as well as the general public, as is evident when looking at social media. But there have also been several instances of violence against queer people by ordinary citizens as also religious organizations and the police in both urban and rural areas across India. There has to be an immediate response to these human rights violations. But the Indian queer movements also need to build up on recent inclusive legislations and efforts to include gender and sexuality learning in educational institutions in order to bring about lasting changes in attitudes towards queer people. Campaigns are also needed to reform the ‘lesser’ laws around sex work, vagrancy, decency and obscenity, which still criminalize queer people. The essential mantra for the way forward needs to be new solidarities with anti-class and anti-caste movements to fight for equity and non-discrimination in all spheres, ideals that the Supreme Court itself upheld in its verdict.

*****************

September 6, 2018 was an overcast, drizzly day in Kolkata. The Honourable Supreme Court of India was to announce its verdict on the infamous Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860. A great legal battle of nearly a quarter of a century was drawing to a close (detailed timeline in inset). I woke up early with fever threatening to engulf me, and immediately remembered that July 2, 2009 had been no different – it had rained heavily and I had been recovering from viral fever. That day more than nine years ago, the Delhi High Court created history by reading down Section 377 to decriminalize all consensual sex among adults in private – irrespective of the gender or sex of the individuals involved.

So the ‘physical’ conditions on September 6 were all pointing at history repeating itself. The significant difference was that the progressive nature of the 2009 verdict had been rather unexpected. We had been hopeful, but never quite expected the tsunami of happiness that the court verdict would swamp us with. It was after all the first flush of success.

This time around, once the hearings were completed in July 2018, few would have bet on a negative judgement by the Supreme Court. Not only were the proceedings over in a record seven days, the comments made by the judges during the hearings were strongly indicative that Section 377 would once again be read down. So when the verdict was announced, the dominant feeling was one of deep relief rather than wild cheering.

Between 2009 and 2018, much else had happened. First, the great shocker of December 11, 2013 when the Supreme Court, having heard both challenges to and defences of the Delhi High Court ruling of 2009, inexplicably reinstated Section 377. The pretext – the law was not unconstitutional, it affected only a minuscule minority of (queer) people, changing the law was the legislature’s prerogative! On all counts the Supreme Court seemed to underscore the book title Supreme but Not Infallible (a collection of essays by several jurists and legal luminaries to mark 50 years of the apex court’s functioning in 2000). Innumerable micro persecutions under Section 377 on a daily basis notwithstanding, nothing had prepared the queer communities, more accurately those part of or closer to the queer movements, to face the blunt might of the State.

Global displays of anger and protestsapart, this setback made the queer movements dig in their heels. There was #377nogoingback into the closet. It was a time for some hard-headed thinking and persisting with all the legal and social options available to make our case. The first signs of hope came in April 2014 with the Supreme Court’s verdict on transgender identities and rights, which in many ways contradicted the Section 377 ruling. All Indian citizens now had the right to self-determine their gender identity, within and beyond the male-female binary, but not live it out in terms of the sex and sexual partners they wanted! Then in February 2016, the curative petitions against the apex court’s 2013 verdict on Section 377 were not rejected and instead referred to a Constitution Bench for consideration.

Finally, the August 2017 judgement on the right to privacy as a Fundamental Right was like a great leap of faith and heart! The fact that one’s sexual orientation had been highlighted as an integral element of the right to privacy showed that the Supreme Court wanted to make amends. The final hearings in July 2018 more or less sealed the deal, and it became more and more a matter of ‘when’ and not ‘if’ Section 377 would go in its current form.

That day came on September 6, 2018. Eventually when the verdict was announced by midday, it made sense for many of us to celebrate and savour the moment in the company of close ones. I postponed plans to join public festivities and stayed at home with my mother, a long-time ally of the queer communities. Her congratulatory message for the community, our domestic worker’s good wishes (she witnessed and served tea and coffee for countless community meetings at my residence), and supportive phone calls from individuals far removed from the scene of queer activism seemed far more invaluable. And it is these reactions that are the core subject matter of this article – the public opinion around Section 377.

In many places in the 493-page verdict, the court itself seemed to address the public at large. While all the judges in the five-member Constitution Bench (consisting of Chief Justice Dipak Misra and Justices R. F. Nariman, D. Y. Chandrachud, A. M. Kanwilkar and Indu Malhotra) hoped for a positive public response to the judgement, Justice Chandrachud in particular said:

“Above all, this case has had [a] great deal to say on the dialogue about the transformative power of the Constitution. In addressing LGBT rights, the Constitution speaks – as well – to the rest of society. In recognising the rights of the LGBT community, the Constitution asserts itself as a text for governance which promotes true equality. It does so by questioning prevailing notions about the dominance of sexes and genders . . .

“The ability of a society to acknowledge the injustices which it has perpetuated is a mark of its evolution. In the process of remedying wrongs under a regime of constitutional remedies, recrimination gives way to restitution, diatribes pave the way for dialogue and healing replaces the hate of a community . . .”

Clearly, the court has gone beyond mere reading down Section 377. Even if not in the guise of formal directives, the judgement provides grist for further far-reaching legal and social reforms. It emphasizes freedom to choose in the intimate sphere, provides an expansive interpretation of privacy and dignity, underscores that stereotyping of queer people limits their right to equality, and talks about combating discrimination in various existing laws. But these can be an acid test for social tolerance and inclusion. Are the various stakeholders up to this challenge? Will the folks at home and citizens out there on the streets or in public transport behave differently with queer people? Will the neighbourhood young men let them alone? Will the bullying in places of learning stop? Will the lawyers and doctors in their chambers, medical staff in hospitals, landlords with flats to rent out, and the police on their beat change their attitudes and actions towards queer people?

Campaigns and discourses over the years

One dare say that what influences public opinion also indirectly influences the judges who interpret the Constitution – they are part of the larger public, surely read newspapers or watch television, and interact with people around them. Moreover, these campaigns and discourses did help frame the legal arguments that were presented in the courts.

Initial struggles for queer visibility:If one looks at the recent queer histories in India, the earliest collective efforts to influence public opinion on queer issues can be traced back to the emergence of support groups in the late 1980s and early 1990s. While the support group activities were primarily for people ‘within’ the queer communities, their journals and newsletters soon began to find their way to book shops and therefore became more publicly available. Bombay Dostin Mumbai and Pravartak in Kolkataare just two examples from this period. Trikone,started 1986 in San Jose, USA and Shakti Khabar,started 1988 in London, UK were among the earliest South Asian diasporic initiatives that inspired similar efforts within India and elsewhere in the sub-continent.

Parallel to these developments was the start of Delhi-based civil rights group AIDS Bhedbav Virodhi Andolan (ABVA) in 1988. ABVA upped the ante through highly vocal and visible activism around HIV and a range of related issues. They joined in with the struggles of sex workers in Delhi to fight off forcible testing for HIV by government agencies, and were instrumental in stalling the draconian AIDS Prevention Bill in 1989 by petitioning the Parliament. They made what were among the earliest efforts to mainstream gender and sexuality diversity into the human rights discourse in India through several landmark actions. The most prominent of these was the publication of Less Than Gay: A Citizens’ Report on the Status of Homosexuality in Indiain November 1991.

This is considered by many as the first meticulously researched compilation and analysis of queer rights concerns in India. It included a charter of demands urging the Government of India to take cognizance of issues that even today the queer movements are yet to advocate for in a structured manner – systematic documentation of human rights violations faced by queer people, decriminalization (repeal of Section 377 as well as relevant sections in the Acts governing the armed forces), civil rights legislation to ensure non-discrimination, recognition of the right to privacy as a Fundamental Right, reform of sexual assault laws to recognize same-sex rape, amendment of marriage laws, provision of ethical and quality mental health, HIV and gender transition services, protection of the rights of people living with HIV, medical curricula revisions, police reforms and responsible media coverage.

Such was the depth and range of the demands that till date many queer activists of my generation prefer to use this unassuming, pocket-sized ‘Little Pink Book’ as one of their main references. For many of us, this was the first guide to learn about Section 377 and understand its full import on queer lives, including its potential as a tool for persecution and blackmail in the hands of intolerant family members, opportunistic intimate partners and unscrupulous police officials. The report also inspired ABVA to file a petition for the repeal of Section 377 with the Parliament in early 1992, but sadly no Member of Parliament of any political dispensation ever brought it up for discussion.

Media interest in issues of homosexuality had been on the rise since the 1980s with the coming out of gay activist Ashok Row Kavi in 1986, the daring (social) marriage of policewomen Leela Shrivastav and Urmila Namdeo in Bhopal in 1987, and subsequently the emergence of queer support groups and journals, and initiatives like those of ABVA. Coverage was generally sensationalized, sometimes sympathetic, rarely progressive and often inaccurate. But it was still ironical and a telling example of barely concealed homophobia that the now defunct Sunday magazine from the Ananda Bazar Patrika media house should depict Less Than Gay as pornographic material in an article in 1992. ABVA filed a complaint with the Press Council of India, but it took nearly two years for a favourable decision to be announced in favour of ABVA. The magazine was eventually forced to publish a rejoinder and an apology note.

ABVA was also behind India’s first public protest against police atrocities on queer people in 1992. Police harassment of queer people in public places like parks was commonplace across several cities (and still is). The immediate trigger for the protest was the arrest of 18 people from Central Park, Connaught Place in the heart of Delhi, a cruising area popular with gay and bisexual men, kothis and other queer people. The arrests were based on mere suspicion of sexual acts being performed in the park. ABVA first organized a protest in the park itself the day after of the arrest, and then on August 11, 1992 outside the Delhi Police Headquarters. A few hundred people gathered for the demonstration that was flashed extensively by the media and was in some ways the precursor of rainbow pride walks and other public events in the years to follow.

A point to note – Section 377 was not the grounds for arrest of the 18 people. Specific sections of the Delhi Police Act dealing with vagrancy, public nuisance or indecency were used. But it was common knowledge that the police would often use Section 377 only as a threat to extort money or get sexual favours done from queer people in cruising areas. The threats would usually work because of the fear of social ostracism, and sometimes even without the mention of any specific law. If a person did not oblige and was indeed arrested, they would be produced before a magistrate but charged under other, ‘lesser’ laws. The case would usually be resolved with the payment of a small penalty. The police would probably never have intended to press charges under Section 377 because of the absence of forensic evidence required to prove that any sexual act ‘against the order of nature’ had at all taken place.

Conferences, solidarities, legal battle, and course corrections: In 1993, Sakhi, a lesbian resource centre in Delhi, and Naz Project, London organized a seminar titled ‘History of Alternate Sexualities in South Asia’ in the Indian capital. The next year, lesbian sexuality was included as a sub-theme at the ‘Fifth National Conference of Women’s Movements’ in Tirupati. This was quite an impromptu development, but the ball was possibly set rolling by the Delhi Group of lesbian feminists who started off their meetings in 1989. Adding to the queer voices were support groups like Counsel Club, Kolkata (started 1993); Good As You, Bangalore (1994); and Humsafar Trust, Mumbai (first registered queer NGO in 1994).

A look at the international backdrop at this time shows that in 1994 Amnesty International became the first international human rights organization to publicly acknowledge the human rights violations faced by queer people. In the same year, the United Nations Human Rights Committee came up with the groundbreaking verdict in Nicholas Toonen Vs. State of Australia that criminalization of homosexuality in the state of Tasmania violated the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

It was in this increasingly busy environment that ABVA revived its legal battle against Section 377 and filed the first writ petition seeking the repeal of Section 377 in Delhi High Court. It used the argument of protecting public health as a means of questioning the constitutionality of Section 377. While it is sometimes argued that the initial legal battle against Section 377 was far too dependent on ‘health’ rather than ‘human rights’ as the crux of the matter, this was not quite a fair assessment. For one, health rights are part of human rights. Second, these were still early years of queer activism and it was feared that an openly queer petitioner demanding their right to have non-normative sexual relations would not get a sympathetic ear from the judiciary. It would be at least another decade before queer individuals came out in court to open a more direct human rights ‘front’ to the legal battle.

Unfortunately, after a few hearings, ABVA’s petition did not gather consistent traction in court and gradually became dormant. Outside the court though there was plenty of action. Humsafar Trust and Naz Project organized South Asia’s first conference for gay and other men who have sex with men (MSM) in Mumbai in December 1994. Queer women’s issues were also discussed, but the participation was by and large male. The conference created a furore and attracted detractors from both right and left wing political parties, forcing the organizers to carefully strategize on the choice of venue (SNDT Women’s University in South Mumbai). Eventually, the conference happened without much trouble and English media coverage was largely positive. It proved to be a huge morale booster for the participants and queer support groups that participated. But its long term legacy for the queer movements was a mixed one.

This conference can be marked for the debut of the identity-neutral sexual health lexicon ‘MSM’ in India. While helpful in advocating with the government for inclusion of the HIV concerns of some queer sections (specifically those assigned gender male at birth) in the national HIV response, it also generated several controversies. For one, it symbolized the inflow of large scale HIV funding into India, the benefits of which largely eluded queer people assigned gender female at birth. Second, it was argued that the focus of many queer support groups shifted to HIV programming rather than defending human rights. In the process, it was also felt that the government’s HIV intervention approach ‘targeted’ at ‘high risk groups’ reinforced the notion that HIV was a gay disease (as also a disease of sex workers or injecting drug users).

In the decades of the 2000s and 2010s, ‘MSM’ as a term also came in for criticism that it invisibilized the unique concerns of transgender women. The formal inclusion of MSM in the National AIDS Control Programme happened in the third phase in 2007. But five years later, when the next phase started in 2012, transgender women’s groups successfully advocated for separate recognition and budgets in the programme. To an extent even gay and bisexual men were critical that the term was reductive and stigmatizing as it seemed to play up only the sexual aspects of their existence to the larger public.

The counter arguments have been that the HIV epidemic and programming around it helped sex and sexuality come out of the closet in Indian society, and that this only strengthened the social and legal arguments for removing or revising laws like Section 377. The second petition against Section 377 filed by Naz Foundation (India) Trust in 2001strongly articulated the deleterious impact of the statute on the sexual and mental health of queer people, including the barriers it created to health service provision and uptake. This is also borne out of the fact that till date HIV prevalence levels among MSM and transgender women are several times higher than in the overall population.

This in turn has helped argue that perhaps the problem was not in queer groups receiving HIV-centred funding, but in the highly medical model of HIV interventions adopted by the government that should have been resisted harder by the queer movements. The government should have supported structural reforms more aggressively to tackle the HIV epidemic than it ever did even in the Naz Foundation case against Section 377 (with the National AIDS Control Organisation being the sole government department arguing for a reading down of the law). It remains to be seen what impact the much belated reading down has on the availability and accessibility of health services for queer people.

The year 1997 is when queer conferencing and movement building took another significant step forward. Stree Sangam (now LABIA), Forum Against Oppression of Women and India Centre for Human Rights and Law, all Mumbai based organizations and Counsel Club from Kolkata organized the ‘Strategies for Furthering Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Rights in India’ conference in November 1997 in Mumbai. This event was among the earliest where the linkages, overlaps and tensions between the women’s and queer movements were discussed at length. It also helped clarify in much greater detail than before how Section 377 affected lesbians and bisexual women in the form of threats and violence by family members and police harassment – beyond its better known impact on gay or bisexual men.

NEW DELHI, INDIA – NOVEMBER 30: Indian members and supporters of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Community hold placards and dances during a Gay Pride Parade, on November 30, 2014 in New Delhi, India. Nearly a thousand gay rights activists marched to demand an end to discrimination against gays in India’s deeply conservative society. (Photo by Arun Sharma/Hindustan Times via Getty Images)

The discussions went well beyond decriminalization to cover issues of anti-discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation (diversity of gender identity was yet to become a focal issue) and the need to redefine the hetero-patriarchal definitions of family and relationships. But the discussions also clarified how any change in laws governing marriage, adoption and even inheritance of property could be stymied by the existence of Section 377. Similarly, the influence of Section 377 on laws around obscenity, representation of women, insurance, housing, and labour rights was analyzed. The post-conference media coverage showed signs of greater balance in the reporting since the earlier years.

The conference had two significant outcomes. One of these was the publishing of Humjinsi – A Resource Book on Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Rights in India(two editions 1999 and 2002). Since Less Than Gay this was the first such resource to be published, complete with conference proceedings, papers on various aspects of queer rights, datelines and bibliographies. It included crucial documentation on the numbers and trends in the application of Section 377 in all its years of existence since 1861, and a heart rending account of the joint lesbian suicides reported in newspapers and magazines between 1980 and 2001. Both these data sets would go on to be part of the submissions and arguments in court in the Section 377 case.

The second outcome was the first systematic nationwide signature campaign against Section 377. ABVA’s petition in Delhi High Court had not made much progress and it was felt that some action was needed to galvanize larger civil society support for the petition and have it reflected in the court proceedings. The campaign managed to collect a few thousand signatures, but the larger gain was a significant course correction in the demand for ‘repeal of Section 377’ being changed to ‘reading down’ of the law. The campaign did recognize that in the absence of comprehensive sexual assault laws Section 377 was the only recourse to tackle not just male-to-male rape but also child sexual abuse and non peno-vaginal rape of women. But child rights groups and activists pointed out that the campaign’s demand for “enactment of laws for addressing all cases of sexual assault and non-consensual sexual acts” along with the repeal of Section 377 was not effective enough since the processes involved in reforming sexual assault laws were likely to be far more complicated and slow moving. There was even a risk, however theoretical, of only the demand of repeal of Section 377 being met by the court in isolation, which could be disastrous for everyone concerned!

This line of thinking on reading down rather than repeal was later reflected in all public articulations against Section 377, and was also adopted by Naz Foundation in its 2001 petition. Moreover, it was crucial in bringing in the solidarities of child rights and women’s rights groups with queer groups, which was reflected in the formation of the Voices Against 377 collectivein 2006. This collective, as we shall see, played a game changing role in broad-basing the socio-legal campaign against Section 377.

While on the subject of solidarities, 1997 also saw a meeting for women who love women included in the official programme of the ‘Sixth National Conference of Women’s Movements’ at Ranchi. Stree Sangam took the lead in organizing the meeting, as also a separate workshop with straight women who supported lesbian and bisexual women’s issues. Maya Sharma, who now leads Vikalp, a support forum for tribal women and transgender people based in Vadodara (Gujarat), and was among the founders of Delhi Group in 1989, points out: “We started raising the concerns of queer women in women-only spaces a long time ago. This was done very gradually through comments and questions during discussions and seminars, issues of single women, forced marriages, divorce and right to maintenance and so on.” Sharma at one time also pushed women labourer’s concerns in a central trade union, and adds that many individual level solidarities were built through networking in such forums. These later contributed to dialogue in more formal forums such as the women’s conferences.

Similarly, across the country, Sappho in Kolkata, eastern India’s first exclusive support forum for lesbians, bisexual women and transgender men that started in 1999, integrated quite successfully with Maitree, a women’s rights network in West Bengal. Seen through the lens of such bridge building, the Indian queer movements were far from ‘HIV-centric’ even in the early years. Besides, these intersectional connections played a major role in the firestorm that was to soon hit the Indian queer scenario.

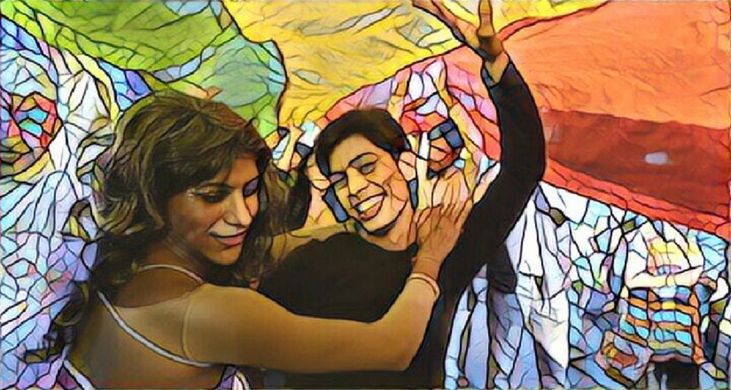

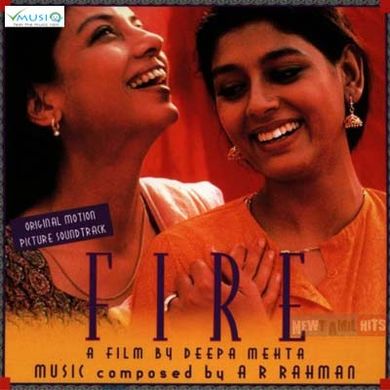

Fireand after: There should not be a hierarchy of events in any socio-political struggle – every bit counts. But to Deep Mehta’s 1998 film Fireshould go the credit of providing an external shot in the arm to India’s queer movements – perhaps not so much the film itself but the civil society response to the controversy around the film. The battle against hetero-patriarchy matured even more with the turn of events around Fire.

Loosely based on Ismat Chugtai’s story Lihaaf (published in 1942), Fire was probably the first Bollywood film to have depicted same-sex relations explicitly, especially sexual and romantic relations between two women. The Central Board of Film Certification passed it without any cuts. But its release in November 1998 set off furious protests by political and religious groups, which branded it as alien to Indian culture and managed to stop the screening of the film in different cities. Several film personalities and human rights activists organized public protests against this not-so-tacit State supported curtailment of the right to freedom of expression, and petitioned the Supreme Court of India. Eventually police protection was provided for the screenings, but it was not until early 1999 that the screenings resumed without further incident. Some feminist and queer support forums were critical of the film for what they felt was a negative depiction of love between two women as resulting from failed marriages. But overall the film created an unprecedented public discourse on homosexuality in India, which had a positive spin-off for the queer movements.

A part of this public discourse was the ‘Campaign for Lesbian Rights’ (Caleri), a loosely knit coalition of organizations and individuals of all sexualities and genders, and one of the most spontaneous and creative responses mounted by the queer movements in India. Most of the campaign activities were carried out in Delhi and Mumbai, but it had a much wider geographical impact within and outside India.

To quote from the campaign report Khamosh! Emergency Jari Hai – Lesbian Emergence (Silence! The Emergency Is On – Lesbian Emergence) published in August 1999: “Caleri coalesced in the days following broad-based protests against the Shiv Sena’s attacks on the film Fire in December 1998. The individuals and groups who met after the protests decided to develop a year-long activist effort aimed at pushing forward the issue of lesbian rights at the level of the people, through a public campaign. The focus on lesbian rights was for a reason – to articulate and nurture troubled connections of lesbians in / with the women’s movement, to talk about the social suppression of women’s sexuality in general, and to address the aspects of lesbian lives that make our struggles distinct from the gay men’s movements.”

The report was published after the first six months of the campaign, and its title was chosen to “[express] our conviction that the trope of Indira Gandhi’s Emergency, imposed in 1975, describes the status of alternate sexualities in India today”. It explained that though the campaign had not developed any goal or a list of rights to be achieved, it had adopted a strategy – Indian revolutionary and political theorist Manabendra Nath Roy’s model of ‘protest-compromise-protest’.

Indian gay rights activists shout slogans during a protest against a Supreme Court verdict that upheld section 377 of the Indian Penal Code that criminalizes homosexuality in New Delhi, India, Sunday, Dec. 15, 2013. Hundreds of gay rights activists gathered in India’s capital and other cities across the country on Sunday to protest a decision by India’s top court to uphold a law that criminalizes gay sex. (AP Photo/Tsering Topgyal)

In Delhi, the campaign was a heady mix of a demonstration outside Regal cinema, one of the venues where the screening of Fire was disrupted; street plays; leafleting outside educational institutions (at some places in defiance of the police’s efforts to stop the distribution), the Supreme Court, government offices and other public places; and public meetings organized by women’s groups to discuss sexuality issues.

In Mumbai, the campaigners had to take into account the likely adverse reaction of political parties like Shiv Sena (the city was their home base), and so opted to raise donations with minimal noise and print 20,000 copies of an anonymous poster titled Why Do Lesbians Need Rights? They found support only from the leader of a political party of Dalits, who put their cadre on the job of pasting the posters on walls. When the police force and Shiv Sena workers started tearing down the posters, the campaigners managed to get a story out in a newspaper on the plight of the posters. This helped turned the tide and attracted support from the larger public.

Over the next fortnight, more funds were collected, another 10,000 posters printed and students, women activists and white collar professionals joined in to put them up in their localities. Having braved out several unpleasant and abusive encounters with the police, the campaigners finally managed to attract the attention of more media, which started reporting on the tyranny of the political parties and police. The campaigners wrote in the Caleri report: “It is a small victory at the cost of immense anxiety and hard labour. But it saved us from a feeling of total despair and sense of inadequacy.”

The report also captured largely favourable feedback to the campaign, including “a letter of support from the National Human Rights Trust, Delhi, an indication that human rights / secular / democratic rights groups were developing an active interest in the agenda of alternate sexuality.” Remarks made by politicians at the highest level to the media were compiled in the report. Minister of State for Information and Broadcasting Mukhtar Naqvi was quoted as saying, “Lesbianism is a pseudo-feminist trend borrowed from the West and is no part of Indian womanhood.” Journalist Bachi Karkaria had retorted, “When you are heir to the breathtakingly permissive Kama Sutra, why confine yourself to the missionary position on sexuality? Homosexuality didn’t need a visa to enter India, it was already here.”

For activist Maya Sharma, one of the high points of the Caleri protests was a banner that simply said “Indian and Lesbian”. Recalling that this was the phase when she was beginning to articulate her sexuality more publicly, she explains that this single banner was both a risk of getting tagged in a restrictive sense and a huge statement of visibility for many of the queer women participating in the protests. Indeed, Fire and Caleri created headwinds of queer women’s visibility and mobilization across India. Resource books like Humjinsi show a spike in media coverage of queer issues more generally and queer women’s issues specifically throughout 1998-99.

Court battle starts afresh: Even as the larger queer political movement in India gathered strength, the legal battle against Section 377 seemed to be going nowhere. By the early 2000s, ABVA’s 1994 petition in Delhi High Court was no longer being pursued. But there was no let-up in reports of queer community members being persecuted under Section 377. Vivek Divan, independent consultant on sexuality and human rights, then a part of the pioneering human rights defenders group Lawyers Collective, recollects the countless run-ins with police narrated by queer people in support group meetings organized by his organization in Delhi.

At that stage, Lawyers Collective had also started initial work on the framing of a national legislation on HIV through countrywide civil society consultations. One of the concerns often discussed was the Damocles’ sword hanging on the NGOs providing sexual health services to queer communities. In talking about safer anal and oral sex or distribution of condoms through field-based outreach and at drop-in centres, they were particularly vulnerable to the charge of abetment in relation to Section 377. Almost on cue, in July 2001, an outreach worker of Bharosa Trust in Lucknow was arrestedwhile distributing condoms in one of the outreach sites. The day after his arrest, the offices of Bharosa Trust and sister NGO Naz Foundation International were raided by the police and queer activist Arif Jafar along with two other colleagues were also arrested under charges related to Section 377 and a host of laws on abetment and obscenity. Jafar, in particular, spent 54 days in prison before managing bail. But the case against him is still pending resolution because of technicalities.[1]

[1]According to Jafar, “Eighteen years down the line my case is still going on. It hasn’t come on trial yet. The police messed it all. As we were only four, they couldn’t show a gang so they randomly picked up seven persons from the streets (interestingly one of those seven supposedly arrested from our office at 16:30 hours was released from Lucknow jail the same day at 20:30 hours). So, technically the trial won’t start till all the 11 accused are present in the court on the same day. Fingers crossed . . .”

About a year earlier, a similar incident had occurred in Almora town in the Himalayan state of Uttarakhand. Sahayog, an NGO working on HIV awareness generation and researching sexual behaviours, was accused of presenting a ‘wrong picture’ about the local communities by political leaders acting as moral guardians. Their staff members were publicly humiliated with no protection coming forth from the administration. The NGO had to shut shop and abandon all its programmes.

Media coverage of the Lucknow incidents, irrespective of language, was deeply homophobic to begin with and fed into the social ostracism faced by the affected NGOs and their staff. For a still very young queer movement, this was quite a moment of despair but, in the words of Jafar, “It galvanized nationwide protests from civil society, LGBT organizations, and drew international attention too. It led to a nationwide movement against the misuse of Section 377 and finally Naz Foundation (India) Trust [at one time affiliated to Naz Foundation International but later distinct from it] with support from Lawyers Collective filed a public interest litigation case in Delhi High Court after a community consultation.”

Observing these developments from the leftist bastion of Kolkata, the only major city where the public had fought off political activists trying to stop screenings of Fire at New Empire cinema in 1998, those of us engaged in queer and sexual health activism still went on an alert of sorts. We were a tad bit more confident of supportive media coverage, but as incidents in later years showed, one could never let one’s guard down with regard to the police and iffy support from government agencies, including those funding HIV interventions and sexual health outreach among MSM. Even at the time of this article being written, in the newly achieved ‘post-Section 377 era’, a queer activist is pursuing a recent case of harassment and abuse by Kolkata Police – simply because he was ‘caught’ in the wrong spot (a lonely pathway), at the wrong time (after dark), and above all with ‘looks’ that made his sexual intent obvious!

Given the context in which Naz Foundation’s petition against Section 377 was filed, it was no surprise that protection of public health once again formed a crucial part of the argument for the reading down of the law. But the larger human rights argument was just as strong – this was articulated in terms of Articles 14 (right to equality), 15 (right to non-discrimination on several enumerated grounds, including sex and with sexual orientation being read into sex), 19 (right to freedom of expression) and 21 (right to life) of the Constitution of India (Part III on Fundamental Rights). Though the Delhi High Court at one point of time famously dismissed the petition on grounds that the petitioners were not an ‘affected party’, it readmitted the case after being directed by the Supreme Court to do so and in 2009 went on to issue a verdict upholding constitutional morality in one of Indian judiciary’s finest hours. By many accounts, this was an outcome of strategic sensitization of media stakeholders outside the court, and broad-basing the legal battle itself within the court.

Divan brings up the formation of Voices Against 377 collective in 2006. It consisted of 12 registered and unregistered groups and a number of queer activists in their individual capacity. The groups included queer forums; student and cultural groups that encouraged on and off-campus dialogue on queer issues; civil society organizations (CSOs) working on child rights, women’s rights, sexual and reproductive health concerns, prevention of violence against women and children, and inclusion of gender and sexuality into school and college curricula; and a human rights lawyers group. Not only was this an excellent example of intersectional conversations and collectivization that caught the media’s attention, Voices Against 377 also contributed significantly to the Naz Foundation case itself.

“In 2006, Voices filed an intervention supporting Naz Foundation’s petition stating that Section 377 violated the Fundamental Rights of LGBT persons. What is not well known is that their intervention also included affidavits from around half a dozen queer persons from different parts of the country – these were personal testimonies of people who had faced custodial rape and torture, extortion, harassment and discrimination around Section 377. More recently some of the newer petitioners have been taking credit for this quite wrongly, but it was the Voices affidavits that first brought in a ‘queer face’ to the legal battle in court,” says Divan. He should know for he was part of a series of queer community consultations in the period 2003-08 that informed the legal arguments of the lawyers.

Outside the court as well, an open letter campaignstarted by bisexual writer Vikram Seth in 2006 roped in more than 100 opinion makers from the literary, academic, journalistic and other fields. Campaigns such as these were crucial because they helped reinforce some of the arguments the queer movements had been fine tuning over the years. One of these was that the case against Section 377 was not just about decriminalizing certain stigmatized sexual acts (read any non-procreative sexual act). It was also about decriminalizing queer gender identities and sexual orientations because the sexual acts in question were associated in public mind only with queer people and their genders and sexualities. The courts too, over the years, had been adding to this bias by interpreting ‘carnal intercourse against the order of nature’ as applicable largely to queer individuals.

In the process, the fact that even heterosexual individuals practised non-procreative sex and that they too were under the ambit of Section 377 was quite lost in popular discourse on gender and sexuality. The media till date has not learnt to not label Section 377 as the ‘gay sex law’. Legally as well, this privilege accorded to heterosexuals would be disrupted only when a woman sought redress under Section 377 for being forced into sodomy (anal or oral sex) because the rape laws did not recognize non peno-vaginal rape; or when a wife sought divorce on grounds of sodomy because family or domestic violence laws did not recognize marital rape in any form.

Ironically, such discrimination only served to highlight the lacunae in India’s sexual assault laws. Some of these gaps were addressed through the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2013 when the definition of rape was expanded to go beyond peno-vaginal rape. But as elaborated in the timeline inset, in a double irony, the new sexual assault laws unwittingly ended up decriminalizing consensual non peno-vaginal sexual intercourse – but only for heterosexual adults! This meant that now under Section 377 literally only queer people could be penalised for consensual non peno-vaginal sex. This violated the constitutional right to equality (Article 14) and proved to be the key argument in the curative petitions filed against the Supreme Court’s 2013 decision to reinstate Section 377.

Coming back to action outside the court for a moment, one needs to look at the role played by rainbow pride marches in India. On July 2, 1999, Kolkata witnessed what is often labelled as South Asia’s first queer pride. The ‘1stFriendship Walk’was organized by a few queer individuals and groups like Kolkata-based Counsel Club and sister NGO Integration Society. It had only 15 participants from Kolkata, Mumbai and a few other places in India. As the name suggests, the objective was to build linkages with both queer-friendly and not-so-friendly individuals and agencies (both government and non-government). The participants spent the day visiting human rights activists, NGOs, the West Bengal Human Rights Commission and the West Bengal State AIDS Prevention & Control Society. In the evening, the media conference was a success well beyond anticipation, with some of the participants having to stage a mock walk outside the meeting venue for the benefit of the cameras. Even as the Caleri campaign was making waves, this initiative grabbed its own share of media headlines and started off what has now become an affair across dozens of cities involving thousands of participants.

The queer pride would have remained a one-off affair, but for its revival in 2003 by Integration Society and other emerging queer support forums. The second walk had 50 participants. Thereafter it became an annual affair with the numbers jumping into a few hundreds and attracting participation from a much wider geographical spread. Till 2007, Kolkata was the only city hosting the pride. But in 2008, Delhi, Bangalore and Mumbai joined in and this expansion grabbed not only renewed media attention but was also remarked upon by the judges hearing the Section 377 case in Delhi High Court. They noted this street-level visibility of queer people as an example of sweeping social changes that the law needed to keep pace with. When eventually the court read down Section 377 on July 2, 2009, it was on the 10thanniversary of the first queer pride, a fact that some of us remembered only after we had spent all our energies in the celebrations.

After first decriminalization and before recriminalization: Many good things happened after the Delhi High Court ruling. Social media stories of queer coming out, family acceptance and social marriages became frequent, more and more queer prides and community events like film festivals and carnivals were organized, and it became easier for NGOs to talk about gender and sexuality diversity in their sensitization sessions.

Then as part of the Kolkata office of SAATHII, an NGO focussed on universal access to health and social justice, I can recollect directing a programme (from 2008-2013) that facilitated two civil society coalitions of sexual minorities and people living with HIV in West Bengal and Odisha states in eastern India. These coalitions were formed to undertake joint advocacy on the health, legal aid and social welfare concerns of queer people, youth, and people infected or affected by HIV. Some of the most interactive and productive sensitization sessions were conducted with healthcare providers, legal aid service providers, child protection officers, media persons, and even police trainee cadets.

While it was not always easy going, given the deeply entrenched biases against anything that questioned hetero-patriarchal values, the number of queer-friendly doctors and lawyers empanelled with us and the list of media persons on our mailing list grew significantly. The State Legal Services Authorities, set up with the government mandate of providing free legal aid to specific marginalized sections, became publicly supportive of queer issues. From the nature and range of queries that the participants in the sensitization workshops had, it was obvious that the Delhi High Court verdict had opened the floodgates of curiosity. For instance, a workshop in 2011 on STI/HIV prevention and treatment with nurses and lab technicians in a remote district hospital in West Bengal turned into an impromptu session on understanding transgender diversities and lesbian health concerns.

At the same time, hate crimes and police atrocities against queer people, particularly transgender women across India, did not quite disappear. Anecdotes of young queer people being forced into conversion therapy kept surfacing from time to time. Provision of HIV services among MSM and transgender women still ran into trouble because of other laws that criminalized them, including laws around sex work.

However, the success of the 2009 verdict had emboldened the queer movements far more than ever before. There were several examples of queer creativity and solidarity, and increasingly on or through online spaces. In 2009, Orinam, a queer support forum in Chennai, started the ‘Open Minds Campaign’ on their website calling for healthcare professionals to sign and disseminate letters pledging that they would “oppose conversion therapy and [support] non-discriminatory, appropriate, and ethical treatment and healthcare for LGBT people” (including international standards of care for gender transition).

Similarly, there was a call for friends and families of queer people to “express solidarity and register opposition to homophobia, biphobia and transphobia”. Queer individuals were encouraged to sign a letter to “promote the visibility of our diverse communities, and [appeal] for non-discriminatory treatment from our family and friends, healthcare establishment, media, educational institutions and workplaces in India”.

The campaign was successful in that it reached out to several queer allies across the country, some of whom eventually became signatories to petitions from parents and mental health professionals submitted in 2011 to the Supreme Court in support of the Naz Foundation verdict on Section 377.

In February 2011, a television channel in Hyderabad called TV9 stirred controversy when it ran a story based on covert operations on gay dating website PlanetRomeo. Dr. Rohit K. Dasgupta, who has researched the growth of digital media in India and its impact on the queer scenario extensively, writes in his book Digital Queer Cultures in India – Politics, Intimacies and Belonging: “[The story] showed a reporter logging into the website and ‘chatting’ with gay men. The respondents were asked leading questions about their sexual lives on the telephone and all of this unbeknownst to them was broadcast on television without blocking out the faces or names of the individuals concerned . . . The programme ended with the reporter concluding that ‘A lot of employees in higher positions, white collared workers, highly qualified students are becoming slaves to lifestyle which is against nature’.” The programme was broadcast more than once despite protests from queer support forums.

News about this development first broke out on the Gaysi Family website for South Asian queer people. The website demanded that TV9 take down the video from their YouTube channel and release a statement promising better understanding and sensitivity towards queer issues. Dasgupta writes: “This was followed by protest events in Hyderabad, Mumbai and Delhi. Adhikaar, a queer human rights organization in Delhi, sent a notice to TV9 under the National Broadcasters Association Guidelines giving an ultimatum to the channel to either redress the situation or risk the threat of following this through to the News Broadcasters Association complaints redressal procedure.”

Adhikaar’s notice made its way to the News Broadcasting Standards Authority (NBSA), which issued a show cause notice to the channel, and subsequently dismissed its defence that its programme was an example of investigative journalism to serve the larger public interest. The NBSA said: “The Programme needlessly violated the right to privacy of individuals with possible alternate sexual orientation, no longer considered taboo or a criminal act; and the Programme misused the special tool of a ‘sting operation’ available only to subserve the larger public interest.” The channel’s claim that the photographs and personal information of the people targeted in the sting operation were publicly available was also trashed as they had entered a membership-only area. This, in fact, raised the issue of how the right to privacy should be understood beyond mere physical or spatial privacy, something that the Supreme Court has elaborated on in its final verdict on Section 377.

The matter was resolved within a month, with TV9 having to pay up a fine of INR 100,000 and carry an apology for three consecutive days expressing regret for having violated the privacy of the individuals targeted by their sting operation and the code of broadcasting ethics. Compared to the Press Council of India’s response to ABVA’s complaint against Sunday magazine in 1992, this was a remarkably faster remedial action undertaken by a media ethics body.

Parallel to these developments, queer activists knew that the battle lines within court were being drawn up once again. Within days of the Delhi High Court ruling, astrologer Suresh Kumar Koushal had filed a special leave petition (SLP) in the Supreme Court challenging the Naz Foundation judgement. Subsequently, 15 other SLPs were filed to oppose the Naz Foundation judgement, a majority of them by religious outfits. Religious figures on television talk shows never failed to condemn homosexuality as a ‘disease’ or a ‘western import’. Negative reactions from the larger public were also evident, with people reacting to the queer pride marches by saying “Why do they have to make a song and dance about it? Do heterosexuals go around telling people who they sleep with?” or “Today they’re asking for decriminalization, tomorrow they’ll be demanding marriage and adoption rights!”

Queer activists were clear in their public stand that though they wanted debate and discussion around equal rights in all spheres in the long run, for the moment they were looking for decriminalization under Section 377. And far from being intimidated by the SLPs filed in opposition to the decriminalization verdict, queer activists and human rights groups like Alternative Law Forum, Bangalore facilitated the submission of several supportive petitions in the Supreme Court during 2009-11. The petitioners included Minna Saran and 18 other parents of queer people; Dr. Shekhar Seshadri and12 other mental health professionals; Nivedita Menon and 15 other social science academics; Ratna Kapur and other legal academics; and filmmaker Shyam Benegal. This was a clear sign of a community not willing to be cowed down, and ever expanding its support base of allies from different walks of life.

Expressions of rage after 11.12.13: The Supreme Court heard all petitions against and in support of the Naz Foundation verdict in February-March 2012. Those closely following the proceedings did not feel quite comfortable with the trajectory of the arguments. A reading of the hearing records would show that the judges did not seem to think entirely on the same lines as the Delhi High Court. Community consultations held in the run-up to the day of the verdict showed cautious optimism at best. Speaking at a panel discussion organized in Kolkata on November 9, 2013 by Kolkata Rainbow Pride Festival, Lawyers Collective founder-member Anand Grover explained: “The most likely outcome will be that the Delhi High Court judgement will be upheld partially – in relation to the right to life, but not the right to equality or right to non-discrimination on grounds of sex because the Supreme Court judges didn’t seem to be in favour of interpreting ‘sex’ to also imply ‘sexuality’ . . .” But no one had expected an outright negation of the Delhi High Court ruling from the apex court.

Among the protests that followed, the ‘Global Day of Rage’ (GDOR) events stand out in their alacrity, spontaneity, and geographical spread. Dasgupta writes in Digital Queer Cultures in India: “The date 11 December 2013 shall remain an important day for the queer movement in India. The Supreme Court delivered its infamous decision putting aside the Delhi High Court judgement and reinstating Section 377, thus effectively criminalizing queer people once again . . . The judgement by the Supreme Court sent shockwaves across the country and the wider world . . . Activists were very quick to respond, and within hours of the judgement, my Twitter and Facebook feed was filled by the outrage expressed by scores of people. In an attempt to organize a collective global action, a Global Day of Rage was announced for 15 December 2013 which would take place all around the world.”

The Orinam website recorded GDOR events in 17 Indian cities and more than 35 globally, including London. “It was fitting and ironic that the colonial centre (London, England) that had created the law in the first place was now joining in to condemn its continued existence,” writes Dasgupta. “The Global Day of Rage was entirely planned and executed remotely using social networking sites such as Facebook and Twitter. Within hours, the statement was written and commented upon by a global Indian queer network. This was happening across geographically specific locations from New Delhi to London aided through network technology . . . By the end of the day, volunteers from almost 32 cities across the world had signed up to take part in the protest. Within a single day, a logo, a press release and Twitter hashtags had been developed to document the event and maintain pressure on the Indian government.”

The GDOR events received widespread media coverage globally. Television channels and newspapers in India focussed on the verdict in a big way. Not surprisingly though, reader responses (as seen in letters to the editor) in popular newspapers were mixed. One reader from Chennai wrote in to The Hindu a day after the ruling: “I welcome the court’s ruling deeming gay sex a criminal offence. The judiciary must uphold our society’s rules of morality, which have taken many centuries to mould. These have evolved over generations of trial and error. It is all very well for supporters of homosexuality to talk about Fundamental Rights and consensus, but the absence of moral rules will lead to chaos and anarchy. We must not misinterpret liberty as lawlessness.”

In contrast, another reader from Kerala wrote to the same newspaper: “Criminalisation of homosexuality is against the right to life as it includes one’s freedom to choose one’s life partner. It is an inviolable right of an individual to choose his partner for life. India needs to recognise gay rights. One must have a broad outlook to analyse the emerging trends and the transformation that society is going through. Homosexuality is a social reality since mythological times, and it has been accepted worldwide. India cannot pretend not to see the reality.”

The GDOR official media release, however, had no hesitation in condemning the Supreme Court judgement: “We are outraged . . . that the Supreme Court can use the phrase ‘miniscule minorities’ to dismiss the rights of LGBT people, thus ignoring the spirit of inclusiveness which is at the heart of the Indian Constitution . . .” The key message of the GDOR ‘campaign’ if it can be called as such was that it was no longer alright to look at queer people as any different from other Indian citizens.

Among the more creative expressions of outrage was the display of placards with protest messages during the ‘Trans Queen Contest North-East 2013’held in Imphal, capital of the north-eastern state of Manipur, on December 14, 2013. The creative round of this hugely popular annual transgender beauty pageant was converted into a ‘protest round’ of sorts. Contestants carried placards that said “Down down Supreme Court ruling”, “We don’t want to go back to 1860” and the more cheeky and futuristic ones “Elizabeth Taylor had eight legal husbands, but I want only one!”

Equality, non-discrimination, inclusion, freedom to choose one’s life partner . . . these are all issues beyond decriminalization under Section 377. One could be forgiven to think that nearly five years did not pass by since 11.12.13 and that the Supreme Court’s final verdict on Section 377 was pretty much a response to the Manipur trans beauty contest demands or the GDOR protests just held yesterday! In a sense the judiciary seems to have eventually been impacted favourably by the continuously evolving campaigns and discourses around Section 377 and queer rights.

But is the decriminalization process complete? What about the other, ‘lesser’ laws used to harass and beat up queer people in public places, especially those with non-normative gender expressions? These laws related to sex work, vagrancy, decency and obscenity may generally attract lesser punishments, but they can be just as dangerous and arbitrary as Section 377. In fact, they relate more to ‘public appearance’ and ‘public behaviour’ and in that sense are tied more immediately to public opinion and reprobation. As the timeline inset shows, small successes have been achieved in reforming some of these extremely regressive laws in Karnataka and Telangana states, but overall and nationally there is a long way to go.

Stepping away from the laws and looking at the larger public opinion itself, all along we have seen a mixed scenario. I recall an online debate many years ago on designing an opinion poll around Section 377. It was argued that framing the question around the ‘natural-unnatural’ axis would be counter-productive compared to framing it around the ‘criminalization’ debate. More people were likely to say that non-procreative sexual acts were indeed ‘unnatural’, but were likely to think twice before agreeing to the idea of 10 years of imprisonment for consenting adults practising such sexual acts. This rings true because by and large the queer movements have had the space to voice their demand for decriminalization under Section 377.

Now that the question of criminalization has been settled to a certain extent, what is the vox populi going to be on issues beyond? The story on-the-ground seems to show that there is already a negative reaction under way. The queer movements are going to have their hands full fighting both ‘lesser’ laws and ‘baser’ social attitudes even as they start talking about equal rights and non-discrimination.

Impact on public opinion – post-Section 377 scenario

As in the case of Delhi High Court verdict in 2009, several positive developments have been reported. On September 24, 2018, directly in relation to the Supreme Court verdict, a lesbian couple in Kerala won the Kerala High Court’s approval that they were within their rights to live together. The family members of one of the women had confined her, and her partner approached the court for an intervention. Given that both women were consenting adults, the court need not have cited Section 377 at all for them to live together. But queer activists feel that the fact that it chose to do so added heft to the judgement and may have set a progressive precedent.

A quick scan of YouTube shows it has been flooded with short videos on public reactionson the Supreme Court verdict. From Chennai to Hyderabad to Delhi, the opinions expressed are mixed and range from outright refusal to accept “something against nature” to ready acceptance – “I’ve absolutely no problem, it should’ve happened by now”. But it is the more politically incorrect and somewhat ambivalent reactions that seem more interesting: “Frankly, if it were to happen in my family, I would’ve a problem” or “I’m out of it, my son’s married!” One person first said “I can’t accept it, it’s unnatural”, but when the anchor explained what the Supreme Court had said, they said “If it’s legally acceptable, then it’s acceptable!”

Somewhere though it is not going to be just a question of law. Faith, religion and spirituality are bound to be part of the mix that is public opinion. Queer support group Sarathi Trust is based in Nagpur city in the heart of India. Nagpur is headquarters to the Hindu nationalist organization Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), widely regarded as the parent organization of the BJP, the political party in power at the Centre. The RSS and BJP have never been unequivocal in their acceptance of non-normative genders and sexualities. A search in both English and Hindi sections of the RSS website shows that the organization may not question the Supreme Court verdict, but there is little acceptance for the issues of homosexuality and transgender identities per se. Anand Chandrani, President, Sarathi Trust says: “Nagpur has always been the headquarters of the RSS. The worry about how we’d be able to conduct our organisational work without being troubled was always a cause for concern. While walking in the first pride of Nagpur [in 2016], I was really scared and worried that we’d be targetted by RSS or some other religious group. Thankfully nothing happened.”

Chandrani recalls the difficulties he had to face in mobilizing enough individuals to register Sarathi Trust in 2006. Later, finding space to operate from was a challenge because nobody wanted to rent out their space for a queer support group. But the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) stepped in to provide support. Today, Sarathi Trust counts the YMCA, National Council of Churches in India (NCCI), Indian Medical Association and a number of healthcare providers and lawyers among its allies for its work on gender, sexuality and HIV issues. Dr. Milind Mane, a BJP Member of the Legislative Assembly of Maharashtra state has always flagged of the three queer pride marches the city has witnessed so far. Currently, Sarathi Trust has its hands full with a spate of sensitization programmes on the Supreme Court’s verdict lined up for students, doctors, lawyers, politicians, teachers and the police. Chandrani feels that media support has always been a crucial factor for Sarathi Trust’s work.

However, queer individuals and groups in other parts of India have not been as fortunate as Sarathi Trust in Nagpur so far. On September 14, 2018, Shillong, the capital of the north-eastern state of Meghalaya, became the first Indian city to host their firstrainbow pride walkafter the Supreme Court verdict. Though largely successful, the march did not pass of without incident. According to the pride march organizers, a religious leader who gives spiritual talks in churches and does Bible readings on Doordarshan television channel, passed unsavoury comments at the walkers. He made lewd gestures while crossing the walkers in his car and wished them to “rot in hell”! The police and the organizers promptly filed FIRs against him. The organizers sought an apology but none has been forthcoming till date.

Rebina Subba, an established lawyer and one of the key figures in the queer movement in Shillong, says: “After the reading down of Section 377, things have changed to some extent. Some of the community people took courage to come out to their family. But for churches the plight still remains stagnant.” Subba feels the Supreme Court verdicts on both transgender identities (in 2014) and Section 377 have given the queer communities some respite. But the tribal customary laws of Meghalaya are indifferent towards the community. Subba adds, “On August 28, 2018, one of the chief executive members of the Khasi Hills Autonomous District Council declared that they won’t recognise transgender people. But we follow a matrilineal system. So what’ll happen in the case of families with transgender children is a big question mark. Will the transgender individuals be denied their property rights? The real fight has just started!”

In the South, even the metropolis of Bangalore has not been spared moral guardianship inspired by religiosity. Jagriti, a theatre group, had to cancel four shows of their play Shiva on October 13-14, 2018 after right wing religious organizations objected to Lord Shiva’s name being associated with a “performance on sexuality and gender”. Ironically, this happened even after the police provided prompt protection. According to a social media post made by the theatre group, they felt that in the face of repeated objections by the religious outfits, it was wiser to be prudent and bide one’s time.

Arif Jafar, who faced imprisonment under Section 377 in 2001, feels a change in public opinion is always going to be a difficult and slow process. He recollects his days in prison: “When we were arrested in 2001, every single media pounced on us with stupid stories. A leading English daily claimed that it was a British conspiracy to convert Indians into homosexuals! We had [sexual health] interventions . . . [they said] we were supplying boys. It drove me insane those days. I just wished that my parents didn’t have to go through all the hell. The judge stated in his [initial] bail rejection order, ‘They’re a curse on society and cannot be set free’. Daily beatings by policemen, denying of drinking water, [being] forced to use filthy black drain water. [It was] really rough but that was their understanding of the issue.

“Society takes you on face value. As I was a believer and prayed during my jail days (nothing unusual, I’d been offering regular prayers since I was five), the attitude of [my] fellow inmates changed and they stood for me against the police. My belief in my faith changed the attitude of some of the policemen. They became my friends, well-wishers, gave me moral support that I would be out. A large part had to do with the supportive civil society outside . . . When Indira Jaising [noted for her legal activism and a co-founder of Lawyers Collective] came along with Anand Grover to fight for [my] bail, the whole jail administration came to see me because they were surprised by this move by Indira Jaising.”

Now that the Supreme Court has ruled on Section 377, what has changed for Jafar? “The police haven’t changed much . . . When one of the journalists contacted police officials of that time [2001], they still maintained that we were promoting homosexuality, supplying boys and had obscene material.” Never mind that the material in question were reputed international publications and journals – Pukaar, an academic newsletter on gender and sexuality; What Shall We Tell the Children, a BBC publication; a safer sex guide to gay sex by Peter Tatchell (now available on Amazon India), and so on.

Neither has the challenge from religious bodies gone away. As in 2001, Jafar continues to face censure from Muslim clerics: “Recently, after the Supreme Court judgement, one of the clerics in Lucknow did a whole lecture on me. I responded that the imam could go on lecturing about me, and after Muharram we could have a long debate. I wrote a long letter to my mosque explaining my side of the story – what I am, why I do what I do, why my rights are important and of many like me.” Clearly, Jafar too is not about to give up: “Last Friday [first week of October] the cleric started to give a sermon on Section 377. I was sitting a few rows away. I stood up and went and sat just next to him. Probably he became nervous that I’d ask him questions. Indeed I have started confronting the clerics with questions like what do they understand of the judgement, what issues worry them, what is the ground reality for queer people . . . We’ve started a new programme called Bridges – Samvaad (which means dialogue).”

There are also gender, class and caste dimensions to Section 377 and its current status. Transgender communities across the country are questioning who exactly has benefitted from the Supreme Court’s verdict. Queer activist and gender and sexuality researcher Ani Dutta shared a post on Facebook on September 21, 2018: “Just two days back, a trans / kothi person in Majhdia, Nadia [district in West Bengal] was assaulted by 7-8 local men, one of whom threatened her saying that the SC verdict on IPC 377 didn’t mean that people like her should now think they’ve gained everything, ‘the verdict can also be taken back . . . we’re going to change you back into a man!’ . . . It’s increasingly clear who benefits most from the symbolic gains of the verdict and who picks up the costs of the increased visibility, scrutiny, and reactionary hostility. Upper class / caste activists party and make endless media appearances, while small-town activists from community organizations do the crisis management and care work necessitated by the backlash (e.g. the members of Nadia Ranaghat Sampriti who dealt with the aforementioned Nadia incident).”

The incidents in Majhdia and other places concerning transgender and genderqueer individuals again bring up the question of privacy. Going by what the Supreme Court has said, a person should have the right to appear and express themselves differently, beyond dominant ideas or norms of gender expression, even in public spaces without fear of harassment or violence. But such an appreciation seems far from being absorbed in the public psyche. While some queer activists feel that the “in private” bit of the verdict was inevitable, others wonder what immediate options have been created for queer people negotiating day-to-day socioeconomic precarity and being forced to live out their (sexual) lives in public spaces.

Jafar argues, “We really need to work closely with the judiciary, police, and law enforcement agencies. We need to make them realize the facts about the larger LGBTIQA communities. They’re ignorant and that’s where the hatred comes from.” But is it just a question of ignorance? What about the power relations law enforcers enjoy over queer people who are unable to enjoy the fruits of decriminalization in the relative security of their homes or dark rooms in party zones?

When seen from the lens of mental health though, the impact of Section 377 can be seen across social divides. In an article Attitudes towards Suicide Worsen the Problem, columnist Bhaswati Chakravorty writes in leading daily The Telegraph (September 27, 2018), “The humiliation of forced sex affects both boys and girls. The same values that condemn raped girls force silence and ‘manliness’ on little boys in similar crises. They are ‘invisible’ too, although a 2007 investigation by the women and child ministry uncovered a shockingly huge number of them. In July 2017, a 13-year-old boy killed himself with rat poison after being raped by a man in a neighbourhood close to Mumbai. It is not just society that enforces silence, the law may help too. A terrible silence laced with the fear of criminal action overlay the world outside hetero-normative society until this month. How many young people have killed themselves, unable to adjust to society’s expectations of ‘normal’ sexual preferences or prevented from living with the one they love?” Activists who have had to double as peer counsellors will often share that material wealth and social standing need not be any match to the oppressiveness of middle / upper-middle class hypocrisies with untold impact on queer lives.

Indian activists of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community react after the hearing at the Supreme Court, at the Humsafar Trust in Mumbai, India, 06 September 2018. India’s Supreme Court ruled on 06 September 2018, that gay sex is no longer a criminal offence. Five Supreme Court judges repealed a colonial-era law (section 377) and legalize gay sex between consenting adults. EPA-EFE/DIVYAKANT SOLANKI

What next therefore?

On two important fronts, surprisingly or not, there have been no big ticket announcements – the political and corporate. While the Indian National Congress and some of the left or left-leaning parties welcomed the Supreme Court verdict, none have shown any inclination for visible inclusion of queer people within their own folds. Election season is round the corner in some of the major northern states and general elections are due in the summer of 2019. It remains to be seen what the party manifestos will say or whether the distribution of election tickets will go beyond tokenism as seen during the West Bengal Legislative Assembly elections in 2016. On that occasion, a number of transgender people were able to vote in their desired genders, but none of the handful of transgender candidates ultimately contested the polls as they felt sidelined.

On the corporate front, barring celebrations around the Section 377 verdict and a few business or civil society initiatives, nothing of far reaching importance has been heard on the development of inclusive human resources policies. After the launch of Tackling Discrimination against Lesbian, Gay, Bi, Trans, & Intersex People: Standards of Conduct for Businessby the United Nations Human Rights Office in October 2017 in Mumbai, clearly much more was expected from business associations like the Confederation of Indian Industry.

Perhaps it will be opportune to make the most of the recent positive developments in the Indian policy environment to push the agenda for non-discrimination. Despite all their shortcomings, the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016; Mental Healthcare Act of 2017; and the HIV & AIDS Act, 2017 have all furthered the cause of anti-discrimination. While the last mentioned materialized rather belatedly as far as protecting sexual health outreach among queer communities is concerned, the Mental Healthcare Act is probably the first national legislation to have specifically mentioned non-discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation.

Another long wait for queer people in India has been the enactment of the Supreme Court’s directives in its 2014 verdict on transgender citizenship rights. A number of states like Karnataka, Maharashtra, Manipur, Tamil Nadu and West Bengal have set up transgender welfare boards, but almost all have a chequered record of functioning. Activists also do not store much hope by the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Bill, 2016. Government efforts to enact the Bill in 2017 were met with vehement protestsbecause it proposed to reverse most of the progressive aspects of the Supreme Court verdict around defining ‘transgender’, gender self-determination, decriminalization and reservations. In contrast, state level transgender policies announced by Kerala and Odisha provide better hope and could be capitalized on in conjunction with the Section 377 verdict.