Stop preaching the converted: Talking feminism in online video gaming!

This article which first appeared on creativetimesreport may seem irrelevant at first sight, but it’s actually a VERY IMPORTANT one! It is a great example of someone who went out of her “comfort zone” and stopped preaching the converted. A strategy at the heart of all good campaigning work. Her example, and the lessons she shares, are enlightening!

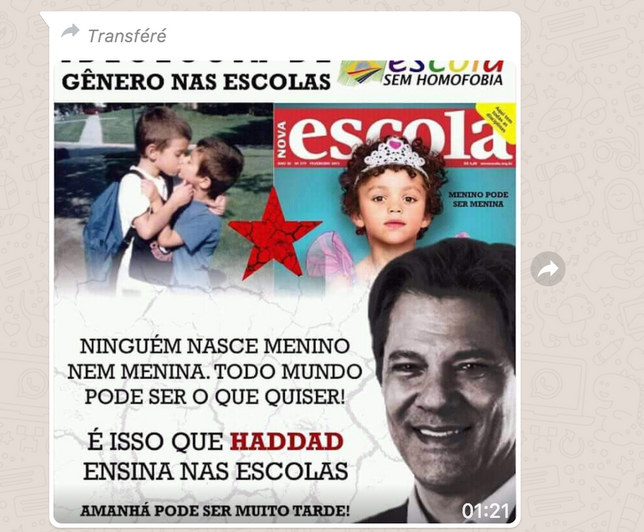

Angela Washko, The Council on Gender Sensitivity and Behavioral Awareness in World of Warcraft, 2012.

[Chastity]:Abortion is wrong and any woman who gets one should be sterilized for life.

[Purpwhiteowl]: should i mention the rape theory?

[Snuh]: What if they don’t have the means to pay for the child and got raped?

[Xentrist]: clearly Chastity in sick

[Snuh]: What if they are 14 years old and were raped?

[Chastity]: I was raped growing up. Repeatedly. By a family member. If i had gotten pregnant i wouldnt have murdered the poor child. because THE CHILD did not rape me.

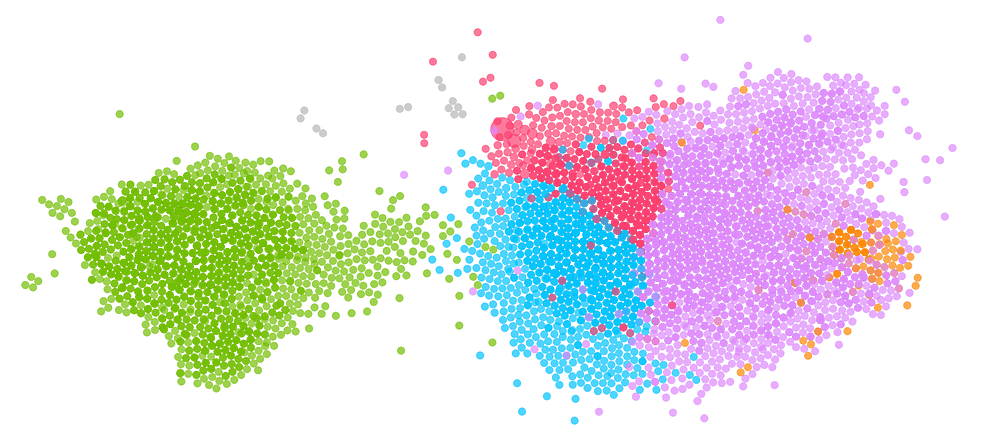

This intense and personal discussion regarding the ethics of abortion unfolded in the lively city of Orgrimmar, one of the capitals of an online universe populated by more than 7 million players: World of Warcraft (WoW). After several years of raiding dungeons with guilds, slaying goblins and sorcerers, wearing spiked shoulder pads with eyeballs embedded in them and flying on dragons over flaming volcanic ruins, I decided to abandon playing the game as directed. Fed up with the casual sexism exhibited by players on my servers, in 2012 I founded the Council on Gender Sensitivity and Behavioral Awareness in World of Warcraft to facilitate discussions about the misogynistic, homophobic, racist and otherwise discriminatory language used within the game space.

As a gamer who is also an artist and a feminist, I consider it my responsibility to dispel stereotypes about gamers—especially WoW players—who have been mislabeled as unattractive, mean-spirited losers. At the same time, I question my fellow gamers’ propagation of the hateful speech that earns them those epithets. The incredible social spaces designed by game developers suggest that things could have been otherwise; in WoW’s guilds, teams come together for hours to discuss strategy, forming intimate bonds as they exercise problem-solving and leadership skills. Unfortunately, somewhere along the way, this promising communication system bred codes to let women and minorities know that they didn’t belong.

Angela Washko,The Council on Gender Sensitivity and Behavioral Awareness: Red Shirts and Blue Shirts (The Gay Agenda), 2014 (excerpt).

Trying to explain to someone who has never played WoW (or any similar game) that the orcs and elves riding flying dragons are engaging in meaningful long-term relationships and collaborative team-building experiences can be a little difficult. Typical Urban Dictionary entries for WoW define the game as “crack in CD-ROM form” and note, “players are widely stereotyped as fat guys living in there parents basements with out a life or a job or a girl friend [sic].” One only needs to look into the ongoing saga of #gamergate—an online social movement orchestrated by thousands of gamers to silence women and minorities who have raised questions about their representation and treatment within the gaming community—to see how certain individuals play directly into the hands of this stereotype by attempting to lay exclusive claim to the “gamer” identity. But gamers, increasingly, are not a homogeneous social group.

World of Warcraft is a perfect Petri dish for conversations about feminism with people who are uninhibited by IRL accountability

When women and minorities who love games question why they are abused, poorly represented or made to feel out of place, self-identified gamers often respond with an age-old argument: “If you don’t like it, why don’t you make your own?” Those on the receiving end of this arrogant question are doing just that, reshaping the gaming landscape by independently designing their own critical games and writing their own cultural criticism. Organizations like Dames Making Games, game makers like Anna Anthropy, Molleindustria and Merritt Kopas and game writers like Leigh Alexander, Samantha Allen, Lana Polansky and others listed on The New Inquiry’s Gaming and Feminism Syllabus are becoming more and more visible and broadly distributed in opposition to an industry that cares much more about consumer sales data and profit than about cultural innovation, storytelling and diversity of voices.

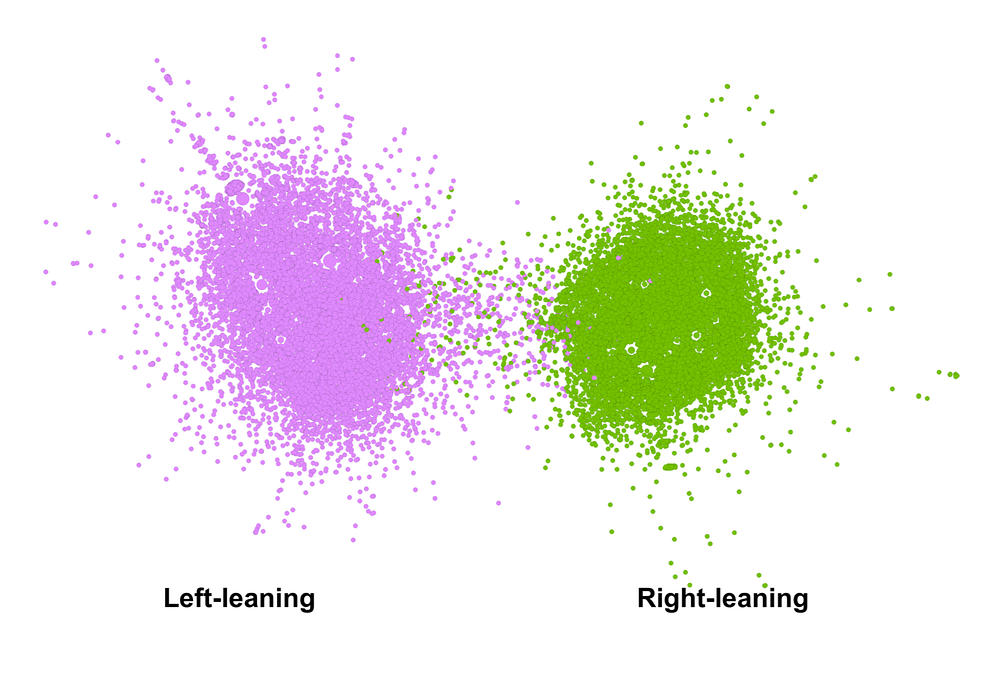

What’s especially strange about the sexism present in WoW is that players not only come from diverse social, economic and racial backgrounds but are also, according to census data taken by the Daedalus Project, 28 years old on average. (“It’s just a bunch of 14-year-old boys trolling you” won’t cut it as a defense.) If #gamergate supporters need to respect this diversity, many non-gamers also need to accept that the dichotomy between the physical (real) and the virtual (fake) is dated; in game spaces, individuals perform their identities in ways that are governed by the same social relations that are operative in a classroom or park, though with fewer inhibitions. That’s why—instead of either continuing on quests to kill more baddies or declaring the game a trivial, reactionary space where sexists thrive and abandoning it—I embarked on a quest to facilitate conversations about discriminatory language in WoW’s public discussion channels. I realized that players’ geographic dispersion generates a population that is far more representative of American opinion than those of the art or academic circles that I frequent in New York and San Diego, making it a perfect Petri dish for conversations about women’s rights, feminism and gender expression with people who are uninhibited by IRL accountability.

Angela Washko, The Council on Gender Sensitivity and Behavioral Awareness in World of Warcraft, 2012.

WoW, like many other virtual spaces, can be a bastion of homophobia, racism and sexism existing completely unchecked by physical world ramifications. Because of the time investment the game requires, only those dedicated enough to go through the leveling process will ever make it to a chatty capital city (like Orgrimmar, where most of my discussions take place), meaning that only the most avid players are capable of raising these issues within the game space. At such moments, the diplomatic facades required of everyday social and professional life are broken down, and an inverse policy of “radical truth” emerges. When I asked them about the underrepresentation of women in WoW—less than 15 percent of the playerbase is female—some of these unabashed purveyors of “truth” have attributed it not to the outspoken misogyny of players like themselves but to the “fact” that gaming is a naturally male activity. Many of the men I’ve talked to suggest that women are also inherently more interested in playing “healer” characters. These arguments are made as if they were obviously true—as if they were rooted in science.

When I ask men why they play female characters, I’ve repeatedly been told: “I’d rather look at a girl’s butt all day in WoW”

Women now have to “come out” as women in the game space, risking ridicule and sexualization, as more than half the female avatars running around in WoW are played by men (women, by contrast, are rarely interested in playing men). Unfortunately this is not because WoW is an empathetic utopia in which men play women to better understand their experiences and perspectives; WoW merely offers men another opportunity to control an objectified, simulated female body. When I ask men why they play female characters, I’ve repeatedly been told: “I’d rather look at a girl’s butt all day in WoW,” “because it would be gay to look at a guy’s butt all day” and “I project an attractive human woman on my character because I like to watch pretty girls.” I found these responses, which were corroborated by a study recently cited in Slate, disturbing to say the least. They also bring to mind Laura Mulvey’s discussion of the male gaze in her influential essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” published in 1975: “In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female. The determining male gaze projects its phantasy on to the female form which is styled accordingly. In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact.”

The simulated avatar woman customized and controlled by a man who gets pleasure out of projecting his fantasy onto her is in strict competition with the woman who talks back—the woman who plays women because, as Taetra points out in the image below, for women it is logical to do so. Women haven’t been socialized to capitalize on—or in many contexts even to admit to having—sexual desires and consequently do not project sexual objects to conquer and control onto their avatars.

Angela Washko,The Council on Gender Sensitivity and Behavioral Awareness: Playing a Girl, 2013 (excerpt).

As I continued to facilitate discussions about the discriminatory language usage on various WoW servers, I realized that the topic generating the most negative responses and the greatest misunderstanding was “feminism.” Here’s a small sample of the responses I’ve gotten when asking for player definitions of feminism (and framing my question as part of a research project):

[Chastity]: Feminists are man hating whores who think their better than everyone else. Personally I think a woman’s job is to stay home, take care of her house, her babies, her kitchen and her man. And before you ask, yes I am female

[Xentrist]: Feminism is about EQUAL rights for women

[Hyperjump]: well all you really need to know is pregnant, dish’s, naked, masturbate, shaven, and solid firm titties. feminism is all about big titties and long stretchy nipples for kids to breastfeed.

[Taetra]: Feminism is the attention whore term of saying that women are better than men and deserve everything if not more than them, which is not true in certain terms. Identifying with the female society instead of humans. Working against the males instead of with.

[Yukarri]: isnt it when somebody acts really girly

[Try]: google it bro

[Holypizza]: girls have boobs. gb2 kitchen

[Raspberrie]: idk like angry more rights for females can’t take a kitchen joke kind of lady

[Defeated]: is that supporting woman who don’t make me sammichs? they need to make my samwicths faster

[Kigensobank]: i dont know if WOW is the best place to ask for feminists

[Mallows]: I think that hardcore feminists often think that women are better lol and they change their mind when they don’t like something that men have that is undesirable

[Alvister]: da fuq

[Misstysmoo]: lol feminism is another way communism to be put into society under the pretense of

protecting women

[Seirina]: Feminists are women who think they are better than men. Theyre nuts. Men and women are equal. We’re just sexier.

[Yesimapally]: Big Chicks who love a buffet but hate to shave their hairy armpits??

[Nimrodson]: i think it’s a word with too many negative/positive connotations to be worth defining

[Dante]: woman are usefull as healer

[Scrub]: yes, women were discriminated against while back, but after many feminist movements the laws were changed. It is now the 21st century and women have all if not more rights then men do. so the feminist activists are doing nothing more then creating drama

The tone of many of these comments reflects what one might find on a men’s rights forum. Recently the gaming and men’s rights communities have overlapped unambiguously, as Roosh V—a so-called pick-up artist dubbed “the Web’s most infamous misogynist” by The Daily Dot—just created an online support site for #gamergate supporters despite not being a gamer himself. I conducted an interview with him for another (seemingly unrelated) project a week before he announced this site.

Angela Washko, BANGED, currently in progress.

Most of the women I’ve addressed in WoW do not see themselves as victims within this system, likely because their scarcity greatly increases their value as projected-upon objects of desire (as long as they don’t ask too many questions) without having it related to the physical body outside of the screen. Among the women I’ve talked to, I’ve found that there are two common yet distinct responses to my questions about feminism and being a woman inside of WoW. Response type #1: “Feminists hate men and feminism encourages physically attractive women to be sluts.” Response type #2: “Feminism is about equal rights for women, but I don’t talk about it in WoW because bringing up issues about the community’s exclusivity compromises my participation in competitive play and makes me a target for ridicule.”

Opportunities to interact online without potential repercussions for one’s offline life are becoming fewer and fewer.

Of course phrases like “get back to the kitchen/gb2kitchen” or “make me a sandwich” can be said in jest, but they nonetheless reinforce conservative viewpoints regarding women’s roles. The overwhelmingly popular belief communicated in this space—that women are not biologically wired to play video games (but rather to cook, clean, produce and take care of babies, maintain long, dye-free hair and faithfully serve their deserving men)—creates a barrier for women who hope to excel in the game and participate in its social potential. This barrier keeps women from being taken seriously for their contributions within the game beyond existing as abstracted, fetishized sex objects. Women who reject this role may be publicly demonized and called “feminazis.”

Unfortunately I did not learn how to turn WoW into a space for equitable, respectful conversation, as I had intended. Instead I came away with some thoughts about how much bigger the issues are than the game itself. Back in the days of dial-up modems, when my family finally realized the impending necessity of “getting the internet,” there was a huge fear of allowing anyone to know “who you really were.” Anonymity was the default then, and protecting your identity was key to avoiding scams, having your credit card information stolen, being stalked IRL or whatever else parents everywhere imagined might happen if someone on the internet knew your “real identity.”

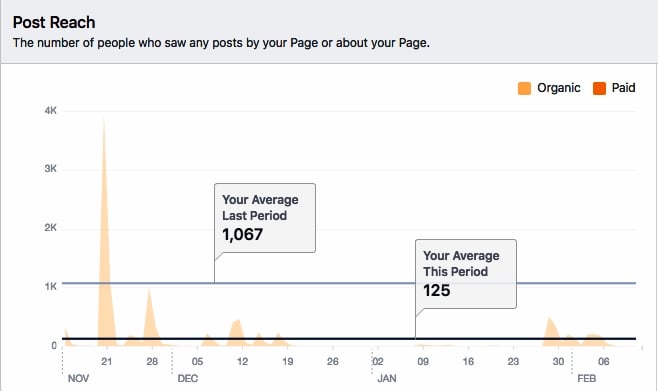

What I learned early on from playing MUD games (text-based multiplayer dungeon games—precursors to MMORPGs like WoW) was that you could actually be quite intimate, revealing and honest with little consequence. There was no connection to your physical self in that kind of setting. But that seems to have changed drastically since the transition from Web 1.0 to 2.0. Web 2.0 has all but eliminated the idealized possibilities of performing an anonymous virtual self, moving internet users toward performing an (often professionalized) online version of one’s physical self (i.e., branding). The possibility of anonymity has disappeared as an increasing number of sites, Facebook foremost among them, require us to use our real names and identities to interact with other individuals online. Opportunities to interact online without potential repercussions for one’s offline life are becoming fewer and fewer.

Angela Washko, The Council on Gender Sensitivity and Behavioral Awareness in World of Warcraft, 2013

Though I had initially hoped to convince many WoW players to reconsider the adopted communal language therein, I quickly realized that this was both a terribly icky colonialist impulse on my part and that its persistence was related to a more complicated desire to hold on to a set of values that is becoming increasingly outdated and unacceptable. Throughout my interventions in the massively multiplayer video game space, I’ve found that WoW is a space in which the suppressed ideologies, feelings and experiences of an ostensibly politically correct American society flourish.

“It’s just a bunch of 14-year-old boys trolling you” won’t cut it—gamers are not a homogeneous social group.”

In many areas of physical space, racism, homophobia and misogyny play out systemically rather than overtly. It has fallen out of fashion to openly be a sexist, homophobic bigot, so people carve out marginal spaces where this language can live on. WoW is a space in which the learned professional and social behaviors (or performances) that we all employ as we shift from context to context in our everyday life outside of the screen are unnecessary. At the same time, this anonymity produces one of the few remaining opportunities to have a space for solidarity among those who are extremely socially conservative in a seemingly unsurveilled environment unattached to participants’ professional and social identities. For the players I talk to, my research project provides a potentially meaningful platform to share concerns about how social value systems are evolving while protected by the facade of their avatars.

Thanks to the emerging visibility and solidarity of visual artists, writers, game makers and other cultural producers fostering a “queer futurity of games” (to quote Merritt Kopas) and more inclusive internet spaces in general, I believe that new spaces will be produced by and for those targeted by #gamergate and its ilk. I hope that efforts will move beyond examining how marginalized groups are represented and move toward creating game spaces that promote empathy. Rather than playing a female blood elf solely because you like the design of her ass, players would be allowed to fully experience the perspective of a person they might not understand or agree with. Perhaps by living as an other in this queer utopian game space, players will come to respect people unlike themselves; at the least, they will have a harder time denying that the experiences of other gamers are valid, acceptable and even worth celebrating.