TikTok – leading LGBTQ youth platform!

TikTok, the app famous for launching newly out rapper Lil Nas X, is a space where many LGBTQ teens feel safe to come out and connect. The best part? Their parents aren’t on it

This Peter may not be Peter Parker, but he is St. Louis, Missouri’s very own Amazing Spider-Man. The 17-year-old recent high school graduate is a member of the Spider-Gang, a cohort of devotees to the comic book character. He’s amassed nearly 21,000 followers on TikTok, the popular new social app whose young users have built massive followings by creating and remixing funny short-form videos.

Peter, who posts under the handle @crashlovesyou, has found his niche slinging webs in a Spidey suit at conventions around the country. He could be a stand-in for Spider-Man: Far From Home actor Tom Holland: He looks, talks and even shares the same name as the fictional webbed warrior. But at the end of Pride Month, Peter cautiously announced one major difference to his TikTok followers.

“TikTok allows us teens to express ourselves more openly, because the majority of our parents don’t know about it,” says Karol, a 17-year-old from Connecticut.

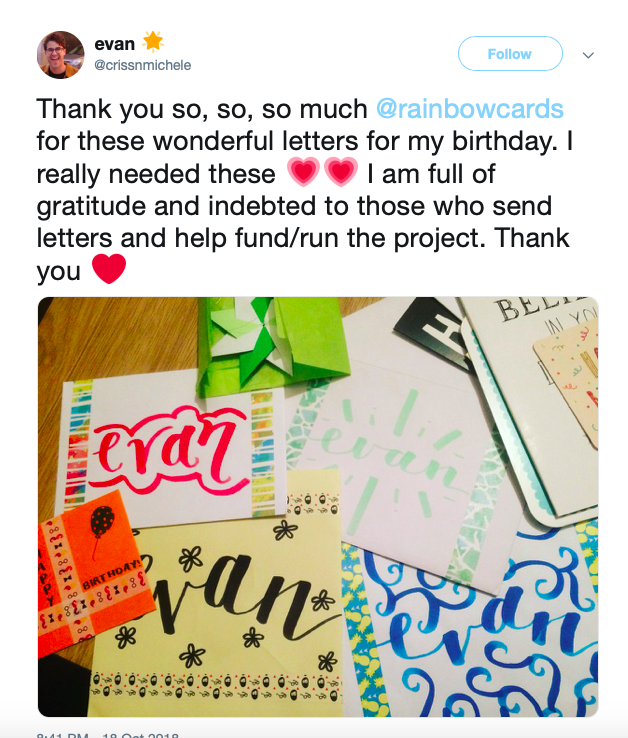

Karol is an up-and-coming TikTok creator with 33,000 followers. But offline, her friends and family don’t know she’s posting satirical videos about being the “disappointing” lesbian daughter of straight Catholic parents. “Parents are on Instagram a lot now,” Karol says. “So in a way, TikTok is definitely ‘gayer’ than Instagram.”

For some LGBTQ teens, the appeal of TikTok is how easy it is to go viral on it. The app functions around a default, algorithmic feed, known as the For You page, which features trending videos curated for each user based on who they follow and what videos they’ve previously liked. Unlike Instagram, TikTok’s default feed is centered on discovery; it’s not filled solely by accounts you follow. As a result, hot new content tends to bubble up quickly. Most teens I spoke with said they had a video go viral within months of creating their account.

While for some users, the intention isn’t always to create “gay” content, TikTok communities form naturally when liking videos with LGBT-inspired hashtags or TikTok’s curated video playlists around themes like “Show Your Pride.” Engaging with LGBT content prompts more LGBT content to surface on your For You page. TikTok is, at its core, a feedback loop. It’s easy to find your people.

That’s why many users create queer content more intentionally. “I wanted to post videos of me being a lesbian so others can relate to my content and push themselves to feel confident with their own sexuality,” says Serenity, 15, a California high schooler with over 107,000 followers.

TikTok’s top queer posts are largely positive. Many are sincere coming-out videos scored to “I’m Coming Out” by Diana Ross; others involve witty commentary on all the various “types of gay guys.” But sometimes the flood of support can turn punitive.

TikTok may be working out its moderation issues, but it remains a leading platform for LGBTQ youth to connect. “Trans men are getting some representation,” Damien says of one of the communities most often left out of LGBT spaces. As for the haters in his comments, Damien couldn’t care less about what they think of his content. “If they can post their progress with bodybuilding, I can [do the same] with my voice. It’s just a screen.”

Whom to follow on TikTok? This list might be helpful

Source: MEL Magazine

!