Why social change needs to be a laughing matter

Reproduced from Wagingnonviolence.org

Struggles against human rights abuses or militarism are rarely linked — in thought or discussion — to humor. As serious matters, they deserve serious, strategic thinking about how to dismantle the power structures that enable them. But what if humor itself is a powerful tool for doing so? In “Laughing on the Way to Social Change,” in the January 2017 issue of Peace & Change, Majken Jul Sørensen explores this possibility in the context of three recent examples of activism in Sweden and Belarus, asking how the use of humor affects the way nonviolent action operates — particularly its ability to disrupt dominant discourses and therefore challenge power.

In the first example, two Swedish activists flew an airplane through Belarusian airspace, dropping 879 parachuted teddy bears with signs reading, “We support the Belarusian struggle for free speech.” A response to an earlier action where Belarusian activists assembled stuffed animals in a central square — bearing signs like, “Where is freedom of the press?” — the parachuting bears ultimately resulted in two Belarusian officials being fired. The second and third involved a Swedish anti-militarist network called Ofog, or “mischief.” In response to NATO military exercises in Sweden, Ofog created a “company” whose purpose was to make these exercises more realistic by providing civilian casualties. Dressed as businesspeople, activists walked through the streets “recruiting” ordinary Swedes for “jobs” as killed, wounded or traumatized civilians. In response to a Swedish military recruitment campaign, Ofog added words to recruitment ads, changing their intended meaning. For instance, on one that said, “Your friend does not want any help during natural catastrophes. What do you think?” Ofog added, “By the military. Other help is welcome.” Using the ambiguity inherent in humor, these actions were able to catch their audiences off guard, spark discussion and bring attention to free speech or militarism in ways different from how logical argumentation could have.

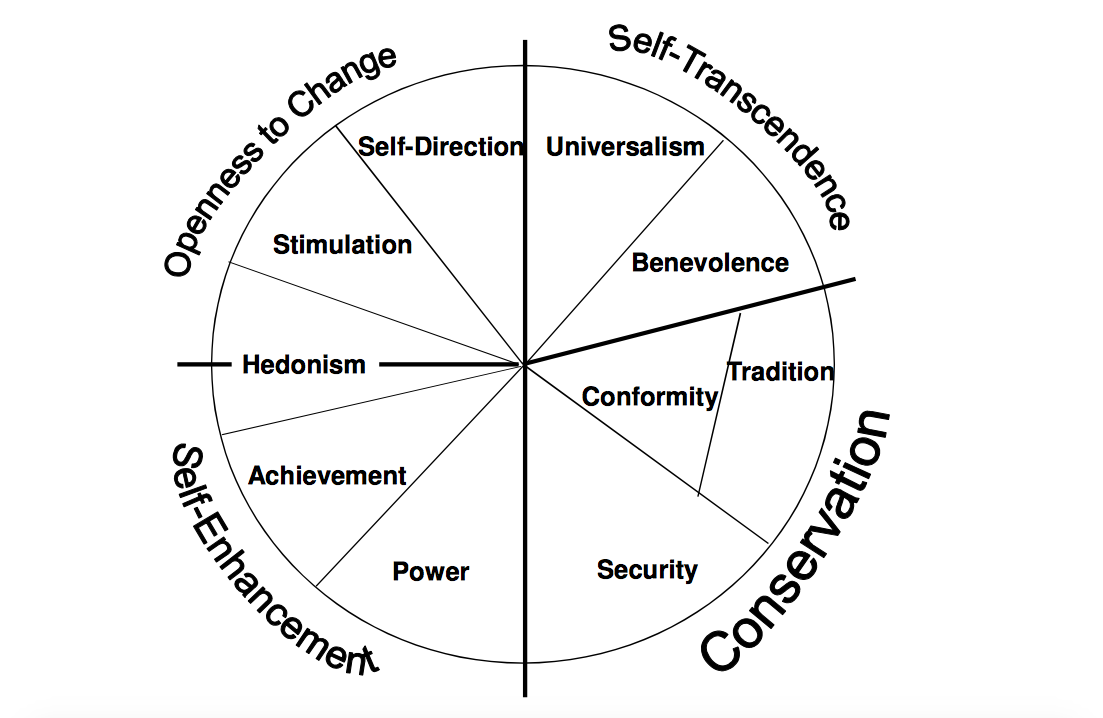

Sørensen examines all three actions from the vantage point of Stellan Vinthagen’s four dimensions of nonviolent action to see how humor might contribute to, or detract from, their operation. The first, dialogue facilitation, refers to nonviolent action’s ability to maintain an openness towards the adversary even in the midst of conflict. On the one hand, a humorous action like those above might inhibit dialogue if observers are “suspicious or annoyed” about the actors behind it or the lack of clarity around its meaning. On the other hand, especially compared to more aggressive forms of resistance, humorous action signals an inherent openness through its playful approach, providing an invitation to dialogue and also lots of “‘material’ for conversation.”

The second dimension, power breaking, is the one Sørensen sees as best served by humor. It is widely understood in theories of nonviolent action that those in power will not give up their power — or even engage in dialogue — unless pressured. Humor is well positioned to break through dominant discourses — themselves forms of power — by disrupting the language and symbols used by those in power to represent reality in a particular way and providing alternative interpretations of that reality. Doing so opens space to question what has been considered “normal” and “natural” — like the need for a military to keep one’s community safe.

The third dimension is utopian enactment: the ability of nonviolent activists to enact, at least momentarily, the new reality that they envision — as when black civil rights activists in the U.S. South engaged in normal, everyday activities like eating or swimming in “white only” spaces, enacting the integrated society they hoped to create. Utopian enactments show that other realities are possible and can create “hope [and] joy” in the midst of anger and despair. Humorous actions are well suited to such enactments, as they engage the imagination and are not bound by the usual constraints of “reality” — as seen in the international solidarity enacted by teddy bears.

Finally, the fourth dimension, normative regulation, re-establishes nonviolence as the norm and violence as an aberration — seen in the training for and maintenance of nonviolent discipline, even in the face of violence. Humor can play a role here in defusing potentially violent confrontations with police, as “a carnivalesque atmosphere” can make interactions “less hostile.” In cases where humorous actions can be interpreted as aggressive or involving ridicule, however, their productive role in utopian enactment and normative regulation may decrease.

While humor may contribute nonviolent action’s effectiveness in some of these dimensions, it may detract from it in others. While parachuting teddy bears through Belarusian airspace challenged the regime’s authority, it did not invite dialogue with the regime — only with the general public. Ofog’s actions disrupted dominant militaristic discourses and engaged the general public in dialogue, but they did not enact the new anti-militarist realities activists envisioned. Most importantly, though, humor — “by playfully twisting the language of power” — provides a tool for activists to engage in what Sørensen calls “discursive guerrilla warfare.”

Contemporary relevance

With the election of Donald Trump to the U.S. presidency, U.S.-based nonviolent resistance has received a massive jolt of energy. Beginning with the Women’s March the day after the inauguration, the resistance has had a lot on its plate: the possibility of nuclear war with North Korea, escalation of war in the Middle East, and the undermining of international organizations and agreements, but also immigrant and refugee rights and protection, a racist law enforcement and criminal justice system, climate change and environmental deregulation, the normalization of sexual assault, an inflated military budget at the expense of crucial social programs, the gun lobby, health care, abortion rights, LGBTQ rights, anti-Muslim prejudice, workers’ rights and economic inequality, and even an emboldened white nationalism — to name a few. In this context, the more we can learn about effective activist techniques — including humor — the more successful we will be at pushing back against the racist, militarist, sexist, science-denying agenda before us.

Practical implications

How can these insights about the use of humor in nonviolent action be applied to current resistance to the Trump agenda, as well as to other nonviolent movements elsewhere in the world? First, it may be useful to conduct an analysis before undertaking an action (as part of a nonviolent campaign) to assess its likely effects on the operation of the four dimensions of nonviolent action, as outlined by Vinthagen: dialogue facilitation, power breaking, utopian enactment and normative regulation. Which of these will be strengthened and which will be weakened through the action — and are these trade-offs worthwhile and useful for the overall goal of the action? Second, similarly, activists should ask themselves: who is/are the intended audience(s) for the action, will different audiences be affected or respond differently, and are these responses useful for the overall goal of the action? Finally, on the basis of this analysis, how might the action be improved to more effectively challenge dominant discourses and spark discussion while minimizing the ways in which it could be read as aggressive or disingenuous?

This article was published in partnership with the Peace Science Digest. To subscribe or download the full issue, which includes additional resources for each article, visit their website.