Hope counters hate in polarized and populist narratives

This article appeared in OpenGlobalRights

Giving people a sense of optimism about and control over their future is the best way to stop populist narratives from taking root.

With the global rise of populism, and far-right narratives increasingly seeping into the mainstream, the most powerful way to challenge hatred is not shouting people down—it is empowering them.

When people feel in control of their own lives, they are more likely to show resistance to hostile narratives, and are more likely to share a positive vision of diversity and multiculturalism. People need to feel listened to and understood, to feel empathy, and to know there is a positive alternative.

Hope not Hate was founded on the very principle that if we are to counter narratives of hate, we must offer hope. Hate is often a response to loss and an articulation of despair. But when given an alternative that understands and addresses their anger, most people will choose hope.

Hope starts with understanding

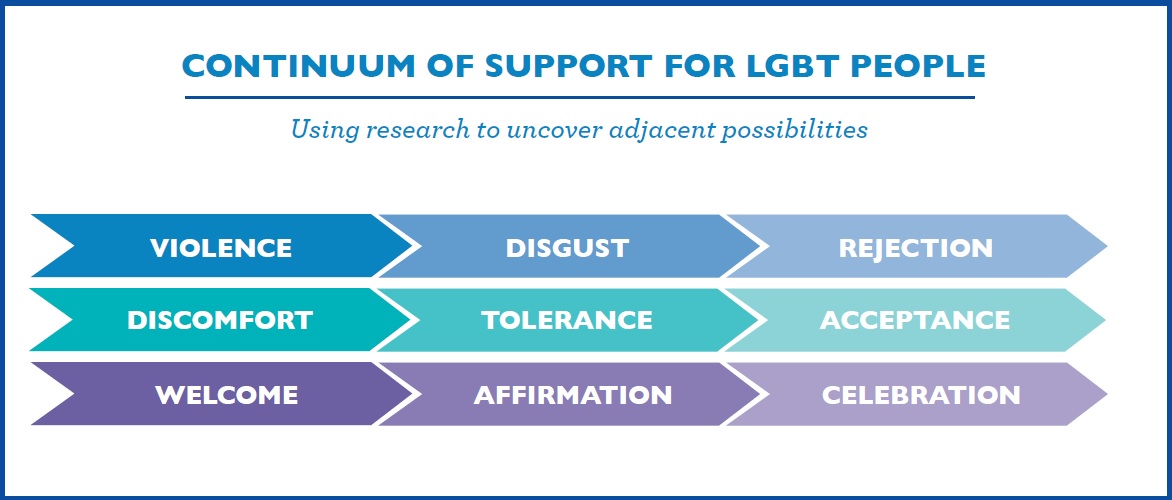

In the polarised immigration debate, with advocates for migrant rights and open borders pitted against aggressive and sometimes violent opposition, it is easy to overlook the majority of people who sit in the middle, holding more moderate and balanced views on migration. Public opinion is not static, but it can move in any direction. If activists fail to engage with these people in the middle, who will not necessarily think the same way and hold anxieties about migration, the only people speaking to them will be those who exploit and amplify these fears.

These conversations are not about tolerating prejudice, and can take on a very different meaning for people of colour than for white allies. There is also a section of the population who hold engrained hostile attitudes towards others—it is simply not possible to change everyone’s mind. But for many of us in the human rights community, fear around having “difficult conversations” is holding us back.

Recently, our organization together with British Future, ran the largest ever public engagement on immigration hearing from almost 20,000 people and travelling to 60 towns and cities across the United Kingdom, from Shetland to Penzance, to talk about migration with normal people.

We found that it was possible to meet a consensus on immigration, and although the conversations we had were primarily for research, the conversations in themselves worked to change attitudes. Through deliberative discussion, and removing the fear of being shouted down, participants developed often left with more positive and nuanced views on migration issues.

We also found that when people talk about immigration, they project national narratives through what they see in day-to-day life. These conversations were often about so much more than immigration but about people’s kids, and their friends, about their problems and frustrations. They were about opportunity, identity and hope, and about where these things had been lost.

Changing attitudes means changing the atmosphere in which they develop

The differences we found in the way that people developed their views on immigration often reflected a broader story about dissatisfaction with participants’ own lives.

In Kidderminster, a market town in the West Midlands, we were told that “the good times have gone”. Lost industry and changing work, local decline, alongside changing neighbourhoods and increased diversity, meant that identity issues and people’s standard of living became intertwined.

To share positive narratives, make people feel good

Having spoken to people up and down the United Kingdom, I found that where people feel in control of their own lives, they are more likely to show resistance to hostile narratives, and are more likely to share a positive vision of diversity and multiculturalism.

Our recent report, Fear, Hope and Loss, pulls together six years of polling from 43,000 people and maps political and cultural attitudes in England and Wales to neighbourhoods of 1,000 houses. Unsurprisingly, we find that it is areas which have lost most through industrial decline, places with little diversity or opportunity, where the greatest enmity toward immigration is concentrated. These are places where up to 61% of over-16s do not have a single educational qualification, where jobs are few and far between, and when work is available, it is precarious and badly paid.

In contrast, we find those who hold the most positive outlook on immigration and multiculturalism are mostly in core cities or elite university towns, prosperous areas where there is ample opportunity.

Resistance to change is not only about a decline in welfare and opportunity, but these anxieties trigger a defensive instinct to protect and reassert a social position. In our conversations, we found that a sense of unfairness underpinned much hostility towards migrants and minorities. A sense that British or English identity is waning becomes more pronounced for those who feel that something has unfairly been taken away. A view that things are working better elsewhere, for other people, for migrants, offered a direction for broader resentment.

Understanding why people feel like they do about immigration is not about pandering to prejudice, but about genuinely understanding what lies underneath, and working to rebuild the communities which have lost the most.

The shock and despair many felt when Britain voted to leave the EU offers lessons on communicating hope. The effectiveness of the Leave campaign was about offering something more, about taking back control. Predicted economic damage of leaving the EU is staggering, but those who want to remain in the EU will not win by projecting doomsday scenarios. The pessimism felt by remainers just does not resonate with people who desperately want change. In a National Conversation discussion in Grimsby, a woman told me that of course things will get better after Britain leaves the EU, because “it could hardly get any worse”. If remainers really want Britain to stay in the EU, then they need to show how things will be better, fairer, and more hopeful than they currently are.

Campaigning with hope

Hope, an optimism based on an expectation of positive outcomes in our personal circumstances, is the best resilience to hate. What gives us hope means many different things to different people, but for many, hope has an economic element. As someone on Grimsby, a fishing town with high level deprivation, told me, hope is knowing “there’s a buffer between you and abject poverty”. While this may not seem to be asking for much, this is not a hope that exists everywhere.

Campaigning with hope means we need to understand what hope means to people, and where it is missing. We need to create the conditions where hope is possible for everyone.

The growing polarisation we see stems from growing divides in our society. But optimism is the best resilience to hate. If we want to shift the debate, we have to start by understanding where these perspectives come from, by engaging in meaningful ways, and by offering hope.