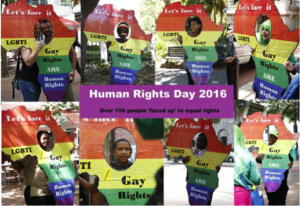

“Let’s Face It – LGBTIQ Rights ARE Human Rights” is the motto that a South African group of activists from the Scalabrini Centre in Cape Town went out on the streets with to challenge the widely-held assumption that homosexuality is “Un-African”.

We asked Neil Goodwin, from the organisers, to share insights into this action, to inspire others.

———–

Neil, tell us more about this action

Too many people throughout Africa don’t recognise the right to be LGBTIQ as a fundamental Human Right. Our campaign sought to champion this right and make it better known and appreciated in Cape Town through a visibility and solidarity drive.

Ruvimbo and I were part of the Human Rights Department at the Scalabrini Centre – one of the largest and most respected refugee outreach centres in Cape Town. Each month hundreds of refugees from across Africa come through the door, for advice, welfare support and to learn English. The Let’s face It Campaign was designed to counter any prejudice and ignorance within Scalabrini’s client base, by bringing the debate about gay rights out into the open.

Through the Scalabrini Centre, we designed a huge Rainbow Africa, with a large hole in the front, where people could literally add their face to the campaign statement ‘LGBTIQ Rights ARE Human Rights’. The idea was to organise ‘Pop-up Prides’ throughout Cape Town, and encourage as many people as possible to ‘face up’ to equal rights, and help beat the silence that surrounds and perpetuates the widespread victimisation of LGBTIQ South Africans and LGBTIQ refugees and asylum seekers here in South Africa. It was a “stand up and be counted” kind of campaign.

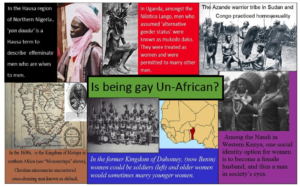

On the back of the Rainbow Africa was a colourful exhibition asking ‘Is being Gay un-African?’, a response to one of the central misconceptions held by people from across Africa that homosexuality came from the West and is therefore alien to African traditions and culture. The display featured a famous quote from Archbishop Desmond Tutu refusing to go to a homophobic heaven. People were invited to ‘FACE THE FACTS’ they had just read, and in so doing, endorse the campaign.

We wanted as many people as possible to ‘face up’ to the need to stand alongside the LGBTIQ community. The year in which we ran the campaign, 2016, marked the 20th anniversary of the South African Constitution, the first in the world to recognise gay rights, and it came ten years after South Africa became the first country in Africa to allow same sex marriage.

Our campaign also came at a time when crucial hate crime legislation was being drafted in South African parliament to outlaw hate crimes against the LGBTI community. The Scalabrini Centre was on the steering committee.

Where did the idea come from?

This was one of my ideas. As an art activist and campaigner, I have been creating lifesized props for some time. Exploring creative ways to add a ‘visual’ to important civil rights issues, in order to promote and encourage debate and to elevate an issue within the media. I’d envisaged creating a huge Rainbow Africa, and the campaign slogan and design just fell into place over the space of a week or so. Luckily, my boss at Scalabrini, Miranda, was open to the idea. There was no dispute at the highest level of the NGO, but there was a degree of resistance at the start of the campaign amongst some of the staff, who felt that Scalabrini ‘shouldn’t be getting involved with those people’.* But overall there was very little debate around it, beyond pitching the idea and costing it. It actually just cost a few hundred rand to create.

* The person who said that (a woman from the DRC) actually put her face to the campaign later on.

What was your approach to roll it out on the streets? and did you encounter any problems?

On the street, we had one essential rule – ask everyone and anyone who passed us to take part. We resisted the urge to only approach those people who ‘looked like’ they might want to take part, and in so doing, captured the very diversity that we sought to champion. We asked everyone. People you ‘might assume’ would tell you to shove off. A rasta-looking guy, for example. A muslim lady with three small kids. A supporter of the Economic Freedom Fighters. A burly looking Nigerian. A homeless man. Everyone. It is unfortunate, but true, that people judge and get judged by their looks. But we found that many people from very different socio-economic, religious, racial, generational and national backgrounds, supported our campaign. We pushed through the stereotypes that so often hold a society down. Especially a divided society like South Africa.

After each campaign outing, we designed an A4 sheet containing a selection of photos from the day, and stuck it on the main stairwell leading into Sclalabrini. The plan was to completely cover the wall in faces and rainbow Africas, to show the thousand or so people from all over Africa who regularly visited the centre each month, the sheer diversity of support for LGBTIQ rights. Quite a number of the visitors, would find themselves on the wall, thereby showing their classmates that they supported diversity. Slowly, through this, we hoped to change the culture within the centre itself from one of silence and suspicion and whispers, to one of openness and understanding.

Here’s a selection of the posters that we stuck up –

Here’s the link to our final campaign video –

You can see all 1,000 faces on our Facebook page

What research went into the conception of this initiative?

We spent a few weeks exploring all the misconceptions around LGBTI people. Being gay was widely believed to be un-African, un-natural, and often ‘evil’. We explored the Bible, the King James bible in particular, textual irregularities and forgotten prohibitions. We discovered that Jesus never mentioned homosexuality once, that Moses in Leviticus also banned haircuts and shellfish, and that ‘abomination’ was a far harsher mistranslation from the ancient Hebrew term toevah, meaning taboo.

We searched for examples of homosexuality in traditional (pre-Christian and Muslim) African culture. We created this poster and meme showing some of the main discoveries

We searched for examples of homosexual behaviour and relationships within the animal kingdom and found hundreds, despite people often saying that it is un-natural to be gay or lesbian.

We looked at countries like Uganda, where homosexuality has been criminalised, and where there has been serious moves to introduce the death penalty. We found that before the three C’s of Colonisation, Christianity and Commerce were introduced by the British, certain Bugandan kings had been openly gay. Though King Mwanga II, the often cited “gay king”, actually burnt young men alive for not having sex with him. So, not the best example of pre-Christian gayness.

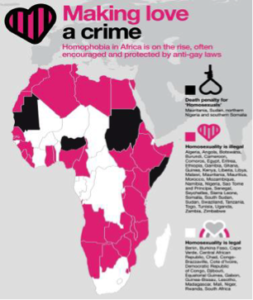

The Christian right in America has lost so much ground in the Northern Hemisphere to a growing tolerance and acceptance of the LGBTI community, that it has shifted its focus and funding towards Africa, where many dictatorships in Zimbabwe, Nigeria, the DRC and especially Uganda, are most willing to accept the cash injection and investment in church schools etc and shift focus and public disquiet away from their leadership by generating moral panic and targeting minorities. We found these two maps amongst the accompanying notes attached to our documentary ‘From the Same Soil’ particularly revealing –

On paper, South Africa might look like an oasis of openness and acceptance on an otherwise hostile continent, but in reality many South Africans are also deeply homophobic, with many examples of hate crimes, often torture and murder, against LGBTI people at the hands of South Africans.

Human rights groups were saying in 2016 that at least 30 women had been murdered in recent years in the country – simply because they were lesbians, and Triangle, a gay rights organization, said that it was dealing with about 10 new incidents of “corrective rape” every week.

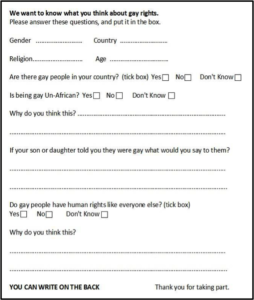

We then decided to carry out a wider survey of Scalabrini’s clients to try and get a better gauge on attitudes. The survey was anonymous, but it did ask for the person’s ‘Age’, ‘Nationality’, ‘Religion’ and ‘Gender’. The questions were put in simple English with ‘Yes’, ‘No’, ‘Don’t know’ options and space to elaborate. Here is the form –

Two of the English classes were asked to take part, as well as a number of random visitors inside Scalabrini’s waiting room area. There was no discussion beforehand, just the simple statement ‘We want to know what you think about gay rights’. A clearly marked box was situated on the stairs within which to post completed forms.

Over one week, more than 150 clients were approached, but only thirty two agreed to take part. According to Nick, who made all the approaches, ‘Some considered the topic was inappropriate to them, unfamiliar and even worse for some, saying it was disgusting. Others were shocked to see such a topic to be launched by Scalabrini Centre or produced at Scalabrini’, which is percieved as a religious organisation.

Of the 32 people who took part, 17 were women and 15 men. . Eighteen of the respondents said that they were Christian (catholic and protestant), and 8 wrote Muslim or Islam. Ages ranged from 19 to 46. Eleven different African countries were represented (the DRC, Congo Brazzaville, Zimbabwe, Angola, Somalia, Libya, Senegal, Cameroon, Tanzania, Mali and Rwanda), all of which, except Rwanda and Mali, criminalise homosexuality and impose harsh prison sentences. In Tanzania up to Life imprisonment, and in certain parts of Somalia, the death penalty.

THE RESULTS

People sometimes claim that there are no gay people in their country in a way that seems to suggest a perceived national ‘purity’ and ‘superiority’, that gayness is somehow a foreign infection or import. We asked the question ‘Are there gay people in your country?’ – 5 answered ‘No’, and 5 ‘Don’t know’. So, the majority answered ‘yes’.

People sometimes claim that being gay is ‘un-African’, that gayness is a Western import. So we asked ‘Is being gay un-African?’ Twelve people ticked ‘Yes’, and 6 that they ‘Don’t know’. So, the majority didn’t think that it was un-African.

When they were asked ‘Why do you think that?’ in the next question people said things like, ‘First of all is against nature because is unnatural’, ‘For me is not good because is abomination’, and ‘That is not right others countries tolerate that but not in my country’, as well as a number of positive comments such as ‘Because everybody have a right to become whoever they want’, and ‘ I don’t have problem with gay people they are people like us’.

In the next question the issue becomes more personal. People were asked ‘What would you say to your son or daughter if they told you they were gay?’ As the issue enters the family space, nearly two thirds of the answers (21) could be construed as being negative, judgemental or punitive in content and tone.’ I will pray and help to not being in this satanic.’ ‘I would say to them they must go out of my house, its not so good for me.’ Also, a refusal to accept this as a possible scenario – ‘They will never told me like that because ma dn my family we save living God.’

On a more positive front, three of the respondents, all woman from South Africa, wrote supportive remarks – ‘I would support them because it is their choice.’ and ‘I will support him or her 100% if its what make him or her happy’, and ‘I would love them and still treat them normally at the same tim make them aware that this is against God’s word.’

The next question asked ‘Do gay people have human rights like everyone else?’ Ten people said ‘No’, and 13 said ‘Yes’. Looking back, I think that that question should have read ‘Should gay people have human rights like everybody else?’ A more personal opinion rather than a potential statement of fact, because in many African countries gay people simply do not have human rights like everyone else.

We then asked, ‘Why?’ ‘Why do gay people have rights like everyone else?’ From the people who said ‘No’, there were these comments – ‘This is the way for the devil.’ and ‘Remember this is the last sin.’ Another person just wrote ‘Bad’. A 24 year old woman wrote ‘Is not easy in DRC to give gay people right because of government’. A 44 year old woman from Zimbabwe stated ‘I think all country not have a human right’.

One person went into quite a lot of detail – ‘No, for example gay people don’t have right to get married at church or in front of the officer, for me its not a right, it doesn’t make sense, it out of normal and I don’t think they can get peace and much love then relationship between men and women as they use to say “I’m gay because I want to be in peace”‘

One of the people who ticked ‘Yes’ wrote, ‘Because there are a lot of countries that give them rights.’ A number of people said things like ‘Because they are human’ or ‘They are just human like any other persons’. Someone wrote, ‘Because they are human, just like a murderer would be. The act is separate from the person.’

It was promising to see positive attitudes, a degree of open mindedness. But religious belief informed a lot of opinion, and there is no escaping from the fact that in order for people to accept gay rights, they would need to accept that their present perception of God or Allah’s teachings are outdated, and misconstrued. Not easy, when millions of Christian right US dollars are currently pouring into the coffers of pastors and dictators across Africa, pushing a powerful anti-gay agenda and reinforcing religious intolerance.

I thoroughly recommend that you watch the documentary – ‘God Loves Uganda’ to understand more fully how pernicious and caustic and deadly this Christian Right crusade has become throughout the continent, even in South Africa.

Beyond religion though, it also makes perfect sense for people to be prejudicial towards a section of society whom they have been conditioned to believe are serious criminals. One study I found useful was this country by country breakdown of the state of LGBTI freedoms throughout Africa. http://www.loc.gov/law/help/criminal-laws-on-homosexuality/african-nations-laws.php

People have family and friends back in countries where to be gay can land you many years in prison. In Uganda, to not report a family member to the police for being gay can land you in jail. It is asking a lot of people, many perhaps from poor rural backgrounds, with little or no formal education, to transcend generations of moral panic and suddenly accept a relationship that they have been told is ‘evil’, and ‘un-natural’, but also paedophilic and a major crime.

From the survey, it was clear that some people recognised and respected the fact that South Africa (at least on paper) sees things differently. I suggested at the time that perhaps cultural orientation programmes could be modified to help reinforce this idea? Perhaps, I said at the time, ‘we need to also find a way to help people appreciate that their religious belief is more akin to a personal opinion, rather than an immovable ancient truth that eclipses everything’.

What were the main expectations in terms of outcomes (media attention, public attendance, academic interest,…)?

Beyond reaching the 1000 faces, the head of our wish list had to be getting the Archbishop Desmond Tutu to become our 1000th face. Initially, his office refused, as he was retired from public life and had recently been in bad health. So, we decided to leave the final ‘face’ symbolically open to him, in respect of all the amazing and powerful campaigning that he has done for LGBTI rights in Africa and throughout the world. We made this decision known during a News24 piece that was filmed about the campaign –

Within a few days, the Arch’s press officer and PA got back to us and agreed to a photo shoot with the Rainbow Africa afterall. So we had our 1000 faces, and an excellent headline to round off the campaign. The City Press, and a number of other media outlets ran with the story – ‘Tutu becomes 1000th face of LGBTI rights campaign’ –

We also wanted to a full page article about the campaign in the Big Issue. And we achieved that too. Alas, we didn’t get the front page, but this was another wonderful lift (enlarge the pic to read the text) –

What were the risks/threats involved and how did you mitigate them (counter demonstrations, police harassment, media indifference, etc.) ?

As a black lesbian woman, Ruvimbo really put herself ‘out there’ during this campaign, and faced abuse and bad vibes on a number of occasions. She never backed away from an opportunity to ‘start a conversation’.

How did you get the campaign done? How much time did it take? how much did it cost? How many people did it involve?

A number of times we had an additional team member taking photos. But there was usually just the two of us involved in this campaign – myself and Ruvimbo. We would try to go out at least once a week (over about a five month period) to a public place, or a meeting or an NGO, even once to a vigil after the Orlando mass shooting, and ask people to lend their face to the campaign.

What did you think where your main assets in doing this action? What worked particularly well and why?

As I have just said, Ruvimbo Tenga was especially good at striking up ‘a conversation’ with people on the street. She was brave enough to put herself out there by speaking to the media about the experience of the LGBTI community in South Africa and Africa, especially the Lesbian community, who were, and continue to be, targetted, raped and murdered in South Africa. It takes great courage to make your face known under such circumstances. And if there is any way for you, the reader, to find a way to support her continual essential work in South Africa, please do so. This campaign owes a huge amount of its success to her, her networking skills, her ability to articulate the issues, and her strong character.

On the other hand, is there anything in terms of capacities that you felt was missing? or that you could have done better? What would you have done differently?

We didn’t have access to a car to transport the huge Rainbow Africa across town, and we didn’t have an awful lot of time to do the activity. We only managed to travel out to the townships on three occasions – Khayelitsha, Langa and .Gugulethu. It would have been good to have based a lot more of our activities in the areas where homophobia and attacks on the LGBTI community are more commonly felt.

Was this action a stand-alone?

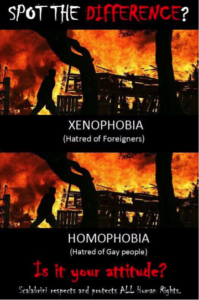

In order to get Scalabrini’s clients to better appreciate and emphasise with the victims of homophobia, we developed a poster campaign that paralleled homophobia to xenophobia, an issue that the Scalabrini clients would understand deeply.

It was difficult to judge the effectiveness of this campaign in terms of changing individual perceptions towards the gay community. But one thing became a lot clearer – Scalabrini’s visible stance on LGBTI rights, around which visitor’s to the Centre could be left in no doubt.

What advise would you give to other people who’d like to undertake this activity?

This activity could be replicated elsewhere in Africa, and also South Africa. You could roll out a number of these large Rainbow Africas quite cheaply and keep the message alive. Perhaps a road trip? Aiming to get to the next target of 10,000 faces nationally in South Africa. A real acid test of whether South Africa is ready to “Face Up” to equality for everyone. We only scratched the surface, but we proved that with the right planning, this campaign device can really add to the debate. People could have access to their own A3 cut out, which they could download from a website, and send in their own image of solidarity.

I think that this stand up and be counted campaign device really helped to shift things a little. It certainly showed me that, if you take time to engage with people and ask the questions that need asking in a creative and non threatening way – you may be pleasantly surprised by the answers that you are given. I know that I was. Hateful and dangerous attitudes need to be marginalised and isoloated, and not allowed to lurk behind a social wall of silence and stereotypes. This was all about diversity, visibility and respect.